“Captive Greece held captive her uncouth conqueror and brought the arts to the rustic Latin lands,” as the poet Horace wrote toward the end of the first century B.C., encapsulating in a few words the fusion of cultures that would decide the future direction of western art and architecture.

The influx of Greek culture into Rome between the late third and first centuries B.C. as a result of the expansion of the empire, which brought southern Italy, Sicily, Greece and Asia Minor within its borders, is the subject of “Roman Days: The Age of Conquest.” This is the first in a series of five projected annual exhibitions at the Capitoline Museums on the development of ancient Roman visual arts and architecture from the early days to the fall of the western empire.

The influx of Greek culture into Rome between the late third and first centuries B.C. as a result of the expansion of the empire, which brought southern Italy, Sicily, Greece and Asia Minor within its borders, is the subject of “Roman Days: The Age of Conquest.” This is the first in a series of five projected annual exhibitions at the Capitoline Museums on the development of ancient Roman visual arts and architecture from the early days to the fall of the western empire.

The historian Livy, a contemporary of Horace, gives a lively account of Rome’s most celebrated reactionary, Cato the Censor, inveighing against the pernicious influence of sophisticated Greek arts on the simple, down-to-earth, homespun rustic ways of the Latins. Cato discouraged Greek philosophers from spending time in the capital (though he himself had a good knowledge of Greek).

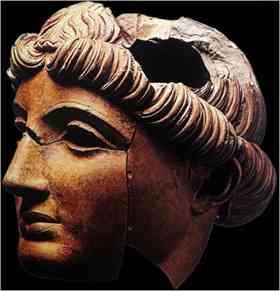

In the same speech, Cato also champions terra-cotta as the traditional Roman material as against the more luxurious marble of the Greeks. There are numerous examples of statuary in both mediums in the opening “Gods and Sanctuaries” sections of the exhibition. Among the terra-cottas is the most complete Roman frieze of its kind from a temple pediment from the mid-second century B.C. It has been assembled from 500 fragments unearthed in Rome in the 19th century, recently “excavated” from the Capitoline Museums’ own storerooms and painstakingly reassembled. The frieze is striking for its preference for terra-cotta over marble, while showing obvious Greek stylistic influences in its composition and architecture.

A degree of loyalty to terra-cotta persisted. Almost all the statues and decorative motifs in the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill were in that material until it burned down in 87 B.C.

“Dangerous for the city, believe me, are the statues brought from Syracuse,” thundered Cato, according to Livy. And, indeed, the Roman conquest of the Sicilian Greek city in 212 B.C. was an emblematic moment in the revolutionizing of the Roman visual arts. Marcus Claudius Marcellus displayed his uncouth Roman side by killing the native Greek genius Archimedes, whose defensive stratagems and machines had made the siege a prolonged one. Returning to the capital in triumph, Marcellus brought back thousands of Greek statues and artifacts of a beauty and refinement previously unseen.

The Greek colony of Tarentum (today’s Taranto) followed in 209, resulting in another great avalanche of artworks into Rome. Significantly, the victor Quintus Fabius Maximus brought back only marbles and bronze statues, leaving behind those in terra-cotta, presumably because he deemed them less prestigious and valuable as booty, even though some were by the renowned Greek artist Zeuxis.

Booty of this kind continued to flow into Rome as the Romans swept through Greece, its islands and Asia Minor. In its wake came thousands of Greek slaves and freemen, artists, architects, intellectuals, doctors and teachers, whose culture and tastes touched every aspect of the city’s life.

One result was a proliferation of portrait sculptures of subjects at various levels of society, a form previously little practiced. Characteristic examples on show include a wonderful bust of Cicero. Politician, lawyer and intellectual, Cicero was thoroughly imbued with Greek culture, but also bears witness to the equivocal, even contradictory attitudes Romans had toward its seemingly all-pervasive influences.

Greek and Roman attitudes to nudity were radically different. Romans were deeply suspicious of the cult of nudity fostered by the Greek gymnasium, both because of its seeming lack of modesty and its homosexual implications. Under Greek influence the depiction of naked Gods and mythological figures became acceptable, but initially not of living subjects.

An area in which this taboo was overcome was in the commemoration of victorious Roman commanders. Heroic nudes of Roman warriors began to appear in second century B.C. The Romans insisted, however, on realistic likenesses. So it was not uncommon for a mature veteran to be depicted with the ideally athletic body of a young man but the face of a much older one, as is the case in one of the heroic (and boldly bald) nude statues on display here.

The second show in the Capitoline Museums’ series, “The Face of Power” in 2011, will be specifically devoted to Roman portraiture. But it can only be hoped that the organizers will improve on the poor presentation of the current exhibition, which contains many important pieces, but meanders through the floors of the permanent collection, is not clearly enough signposted and offers inadequate explanations on the panels.

The RavennAntica Foundation has set a high standard in content and bilingual presentation in its annual exhibitions on various aspects of ancient life and art at the Complesso di San Nicolò. “Histrionica: Theaters, Masks and Spectacles in the Ancient World” is an exhibition of more than 120 works, including statues, frescoes, masks and ceramics.

Theater was another area in which Greek models were paramount, although forms of indigenous drama did exist. The “Fabulae Atellanae” or “Atellan Farces,” rough comedies derived from Etruscan traditions and those of Atella in the Roman Campagna, were popular in Rome by the third century B.C. A remarkable set of plaster masks being shown for the first time ever, excavated from a shop in Pompeii (probably sales samples), have been identified as those of Atellan stock characters: Bucco, the ridiculous braggart; Maccus, the gluttonous rogue; Pappus, the old fool; Dossenus, the shrewd hunchback, and so on. (The Latin word “persona,” and hence “person,” was derived from the Etruscan “Phersu,” a masked figure that appears in tomb frescoes.)

More complex forms of comedy and tragedy derived from Greece. The comedies of Plautus (254-184 B.C.) even have Greek characters and settings, the playwright “transferring Athens to Rome — without the architects,” as is declared in one of his prefaces. Tragedy was equally indebted to Greece, although it acquired Roman settings and characters.

Theater in Rome did not fulfill the religious and civic roles it did in Greece but was immensely popular as mass entertainment. Images related to the theater became ubiquitous as motifs embellishing buildings, furniture, frescoes, household goods and as garden ornaments. The masks worn by the performers were of perishable fabrics, wood and leather, but versions made in terra-cotta and marble survive in excellent condition (more than 50 of these are on show here).

Roman theaters were for long temporary wooden structures (there were fears that permanent ones would become meeting places for sedition). The first one in marble and brick in Rome was built by Pompey as late as 55 B.C. Unlike Greek theaters, which used natural inclines of hillsides to create their amphitheaters, Roman theaters were free-standing. This form of architecture created a series of blind arches (“fornices”) at street level, incidentally providing dark places for prostitutes to ply their trade — and bequeathing to the world the word “fornicate.”

Roman Days: The Age of Conquest. Capitoline Museums, Rome. Through Sept. 26.

Histrionica: Theaters, Masks and Spectacles in the Ancient World. Complesso di San Nicolò, Ravenna. Through Oct. 10.

Author: Roderick Conway Morris | Source: New York Times [August 13, 2010]