What’s the sound of one hand clapping? This famous meditational question was first framed as “What is the sound of one hand?” by Hakuin Ekaku, an 18th century painter and Zen master whose work is showcased at Japan Society through January 9, 2011 in The Sound of One Hand: Paintings and Calligraphy by Zen Master Hakuin.

“Although a major figure in Japanese art and widely regarded as the most important Zen master of the last 600 years, Hakuin is virtually unknown to American audiences today—a situation Japan Society intends to redress with this, the first retrospective of his work ever to be seen in the United States,” says Joe Earle, Director of Japan Society Gallery.

“Although a major figure in Japanese art and widely regarded as the most important Zen master of the last 600 years, Hakuin is virtually unknown to American audiences today—a situation Japan Society intends to redress with this, the first retrospective of his work ever to be seen in the United States,” says Joe Earle, Director of Japan Society Gallery.

The Gallery at Japan Society has co-organized the exhibition in collaboration with the New Orleans Museum of Art, where the exhibition will be presented February 12 to April 17, 2011, before traveling to Los Angeles County Museum of Art from May 22 to August 17, 2011 (in 2 installments).

For the showing, exhibition organizers and noted Zen scholars Audrey Yoshiko Seo and Stephen L. Addiss have gathered 69 scroll paintings by Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768) and nine by his major pupils from public and private collections in Japan and the U.S.

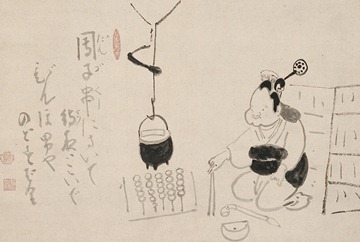

The selection brings into public view a masterly body of work, one in which deftly executed, fluid lines, delicate ink washes, quick, rough strokes, and spidery calligraphic marks serve to capture the energy of life and the playfulness and spiritual intensity of Zen practice.

The exhibition traces Hakuin’s development from the more linear works of his early period to paintings and calligraphy of massive power from the final two decades of his life.

Among the most delightful paintings on view are those that depict mundane objects and activities, sometimes in the guise of myths and folk tales, whether it be a monkey on a tree limb, two preening foxes dancing, or a Buddhist pilgrim perched on the back of another to write on a high wall.

In the painting Blind Men Crossing a Bridge, the tiniest of brush strokes manages to conjure up halting steps and uncertain balance in a progression along a wooden bridge—the latter summoned up in one broad, bold, horizontal stroke. A similar economy enlivens other works, such as Shoki Sleeping, which captures a tub-bellied folk deity, boots on, snoozing.

One of Hakuin’s favorite subjects was the happy-go-lucky wandering monk, Hotei. Featured in the exhibition is a painting of Hotei asking “What is the sound of one hand?” along with 17 other depictions of the bumbling monk as everyman: sleeping, meditating, riding in a boat, shouldering a large mallet, and—most unusual of all—floating as a kite in mid-air.

Hakuin would have created pictures of these folk characters—popular figures in Japanese culture—as a way of reaching out to ordinary people. But he created works with Zen subject matter as well, including portraits of Zen patriarchs executed with dramatic, virtuosic brushwork.

Also featured in The Sound of One Hand are pictures created for followers of non-Zen forms of Buddhism, including one of the deity Monju, who represents wisdom and the power to cut through all obstacles. This is one of Hakuin’s most finely painted scrolls, showing how delicately he could wield his brush.

Humorous wordplay is an inextricable part of many of the featured works. The punning lines in a painting of a small singing bird poke fun at human behavior, and a flowing inscription in a drawing of Otafuku, the Goddess of Mirth, slyly connects the goddess’s skewered morsels to ideas not yet absorbed by a man with a closed throat (i.e., one not yet open to the teachings of the Buddha.)

“Hakuin integrated painting and calligraphy in a manner that had never been done before. Characters would become part of a drawing, or a drawing would be entirely comprised of characters,” notes co-curator Stephen Addiss.

Life and Art as Zen Practice

Perhaps because Hakuin’s paintings and calligraphy were an extension of his role as a teacher, as a rule he did not create art for the marketplace, patrons, or temples.

Most of the paintings on view in this exhibition were given to lay followers as gestures of encouragement or to fellow practitioners in recognition of spiritual advancement, with certain subjects deemed particularly suited as Zen teaching tools for individuals. Others works were probably given to monks from other temples who admired Hakuin’s Zen teachings.

Despite spending most of his career in a small rural temple, Hakuin revitalized Zen practice throughout Japan. “He deepened monastic practice by insisting upon post-enlightenment training and by consciously and enthusiastically reaching out to lay parishioners in new ways,” says co-curator Audrey Yoshiko Seo.

“Hakuin believed that the Zen experience must be taken back into the world in order to flourish and fully aid people in their journey. His influence was so great and far reaching that it is impossible to imagine contemporary Zen practice without him,” adds Addiss.

Source: Art Daily [January 02, 2011]