The Greek Islands are about beaches, you say, with maybe a ruin or two to satisfy the nagging cultural imperative. But then, I suspect, you haven't been to Patmos.

This northern Dodecanese island is a special place. Its claim to fame lies in a unique mystical event that took place at the dawn of Christianity, and is embodied in the looming apparition that hovers like a benediction above the island.

This northern Dodecanese island is a special place. Its claim to fame lies in a unique mystical event that took place at the dawn of Christianity, and is embodied in the looming apparition that hovers like a benediction above the island.

You can see it as the boat arrives in the pretty harbour of Skala: a halo of whitewashed houses, encircling what looks like a huge, crenellated castle of volcanic stone.

Leaving Skala's picturesque cafes, ouzeris and tavernas, a drive through thick pine forest will lead straight to it; not a castle at all, but the imposing 11th-century Fortress Monastery of St John the Theologian.

The story of St John - sometimes referred to as the Apostle or Divine - is central to Patmos. Exiled by emperor Domitian in AD 95 to this backwater, he settled in a cave, where he had the apocalyptic vision recounted in Revelation, the final book of the New Testament.

Nothing much more happened until 1088, when the Blessed Christodoulos, a monk, acquired Patmos from the Byzantine emperor Alexios komnenos, and founded the Monastery to honour St John. This was to become the nucleus of the island and, thanks to the strict observance of tradition and the absence of mass tourism, little has changed.

With historian Antonis Dimas as my guide, we stopped at the cave where the story began. Mass was in progress, and we followed a baritone chant to where the faithful thronged the entrance, piously elbowing their way to the altar for blessing.

Above the bobbing pates, I could see the triple cleft in the roof of rock through which St John heard the voice of God, and glimpsed the famous icon of the revelation above the spot where the Saint rested his head.

Later, we proceeded to the Monastery, entering the small, pebble-paved courtyard to find it empty, save for black-robed, white bearded monks. Suddenly, we were light years from the 21st century.

Antonis indicated one elderly monk sitting beneath an elegant arcaded bell tower. 'he used to be a ballet dancer in London,' he assured me.

Antonis indicated one elderly monk sitting beneath an elegant arcaded bell tower. 'he used to be a ballet dancer in London,' he assured me.

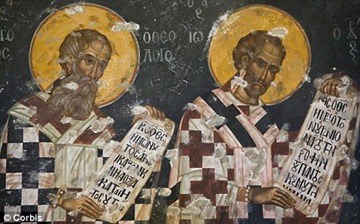

Trying to banish the vision of the holy father in tights, I passed through 900-year-old carved doors into the main chapel; a glorious incense-filled twilight lit by candelabra and silver lamps, every wall covered in frescoes, some as old as the 12th century.

But the monastery's greatest treasures are housed in its museum: from 5th-century codices and magnificent medieval icons to episcopal regalia and the decree by Alexios komnenos granting Patmos to Christodoulos in 1088. here, too, you will find an ecce homo - a portrait of Pilate presenting Christ to the crowd - purportedly by el Greco, which is solemnly paraded through the streets during Holy Week.

From the terraces, this hermetic world opens onto spectacular vistas over Patmos and the misty outlines of neighbouring islands. We wandered down through the labyrinthine alleys of medieval Chora, a UNESCO World heritage site, free of cars and tourist friendly accretions.

Quirky white houses, huddled around the monastery for safety, cascade down the hill.

'This way, inhabitants could leap across the rooftops and into the fortress during pirate raids,' Antonis explained.

In time, refugees from Turkish-invasions in Constantinople, Rhodes and Crete arrived to seek the Saint's protection and, by the 17th century, prosperity spawned grand villas built around internal courtyards.

In time, refugees from Turkish-invasions in Constantinople, Rhodes and Crete arrived to seek the Saint's protection and, by the 17th century, prosperity spawned grand villas built around internal courtyards.

Now largely the preserve of wealthy Athenians, the uniform white walls trailing blazing bougainvillea give little clue to the splendour that lies within.

The South is home to the fine sandy shore of Psili Ammos, near the cape of Genoupas - the evil magician against whom, legend has it, St John waged war (the Saint won).

But the dentellated north coast offers greater choice, and we headed to Livadi Tou Pothitou, whose pebbles are shaded by tamarisk trees. Brace yourself for icily transparent waters.

One memory will remain indelible. At the seaside taverna on Lambi - a beach so renowned for its unusual pebbles that an unmissable sign forbids the removal of a single stone - I was nibbling rare seaweed and freshest octopus over a glass of ouzo, when I heard a commotion.

Four cars came screeching to a halt, and disgorged a dozen priests onto the beach. I watched as, trailing their robes in the surf, they upended their hats like buckets and began frantically shovelling pebbles.

A senior cleric (he wore an impressive pectoral cross) looked on, and gave me a sheepish grin as I made a dash for my camera. Too late. The beach-raiders raced past me into their cars cradling their booty and sped off, like an orthodox version of The Italian Job, just leaving a cloud of dust behind.

Patmos is indeed an island like no other.

Author: Teresa Levonian Cole | Source: Mail Online [January 07, 2011]