Egyptian mummies used to be among the most popular displays in British museum collections. But their days as a visitor attraction may be numbered. Increasingly they are being secreted away by curators, hidden away from the public without consultation.

In the coming year, Bristol City Museum & Art Gallery will publish its first policy specifically on the use and display of human remains. It is clear from the draft that staff are increasingly sensitive about exhibits of ancient bodies and skeletons. Recommendations include erecting signs to "alert" visitors that such material is on display – and reconsidering whether to show it at all.

In the coming year, Bristol City Museum & Art Gallery will publish its first policy specifically on the use and display of human remains. It is clear from the draft that staff are increasingly sensitive about exhibits of ancient bodies and skeletons. Recommendations include erecting signs to "alert" visitors that such material is on display – and reconsidering whether to show it at all.

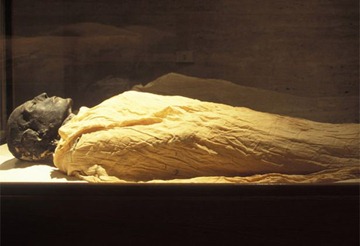

Already the museum has dramatically altered what is on display. It used to present its celebrated collection of Egyptian mummies in open sarcophagi, but now keeps the lids semi-closed because, curators say, that is more respectful. Visitors are only permitted to see photographs of unwrapped mummies and they have to positively opt in to this by switching on the light.

Elsewhere in the museum is a rare skeleton of a young man who lived in Britain during the Bronze Age, 3,400 years ago. He is in a case with a label warning: "This display contains human remains."

This cautious approach is not an isolated case. In the past five years, 17 museums in Britain have issued specific policies on human remains, codes that were unheard of a decade ago. Some, like Manchester Museum, have shrouded Egyptian mummies in white sheets while keeping them on show, only unveiling them after public protest.

This cautious approach is not an isolated case. In the past five years, 17 museums in Britain have issued specific policies on human remains, codes that were unheard of a decade ago. Some, like Manchester Museum, have shrouded Egyptian mummies in white sheets while keeping them on show, only unveiling them after public protest.

Others choose to show them away from the main galleries. The Museum of London says: "As a general principle, skeletons will not be on 'open display' but located in such a way as to provide them some 'privacy'. The museum will normally not allow its holdings of human remains to be photographed or filmed for external media purposes."

Human remains have been used in research and in museum displays for more than 200 years. Most museum-goers expect to see them on display. Around 90 per cent of respondents to an opinion poll of 1,000 people commissioned by English Heritage said they were comfortable with keeping prehistoric human remains in museums.

Indeed, such remains are big crowd-pullers, especially for families with young children. Programmes such as Meet the Ancestors, the TV documentary series, with the archaeological excavation and scientific reconstruction of human remains, win impressive viewing figures.

Indeed, such remains are big crowd-pullers, especially for families with young children. Programmes such as Meet the Ancestors, the TV documentary series, with the archaeological excavation and scientific reconstruction of human remains, win impressive viewing figures.

But this may be about to change. The practice of using remains as exhibits is under attack from an unlikely source. For what is remarkable about this new sensitivity is that it has not come from public demand, but from the top down – senior curators are writing the policy.

The explanation lies in the wider international and historical context. Over the past 30 years human remains have become the focus of various campaigns in North America, Canada and Australasia. Indigenous groups, archaeologists and anthropologists campaigned for the repatriation of human remains to culturally affiliated groups as a way of making reparations for colonisation and the impact of settler society, and as an opportunity for these groups to write their own histories.

In the late 1990s a similar debate took place in Britain. Eventually, partly as a result of the Alder Hey organs scandal, the Human Tissue Act 2004 was passed. This included a clause to permit the transfer of human remains from specific museums, which had previously been forbidden.

In the late 1990s a similar debate took place in Britain. Eventually, partly as a result of the Alder Hey organs scandal, the Human Tissue Act 2004 was passed. This included a clause to permit the transfer of human remains from specific museums, which had previously been forbidden.

But museums do not usually let human remains go as they constitute valuable and often unique research material. And the removal of this important material puts the role of museums – to develop knowledge about past peoples, and share it with the world – in question.

The controversy in the UK is different in two important respects. First there was weaker external pressure on institutions compared with Australasia, America and Canada. A 2003 survey conducted for the Human Remains Working Group, a Government appointed committee, categorised claims from overseas groups on institutions as "low". Indeed, they only found 33 such requests on English institutions, seven of which had already been agreed to, and others that were repeat claims from the same group.

In Britain, high-profile demands that museums deal differently with human remains, which have resulted in law changes and major repatriations, are not primarily due to pressure from overseas groups. Such claims have not, in fact, been that significant here. And in fact all human remains have become the focus for professional activism.

Museum professionals were once gatekeepers, guarding and protecting collections. So why are some increasingly uncomfortable about displaying remains, continually questioning its ethics, covering up skeletons, removing them altogether, or erecting warning signs?

In the past 40 years, the foundational principles of museum institutions have undergone critical scrutiny and this has led to a crisis of purpose. Museums were formed in the time of the Enlightenment (the 18th century), when the pursuit of knowledge was considered paramount. While there has always been some hostility towards the principles of this period a number of intellectual trends since the late 1960s have consolidated this critical view.

In the past 40 years, the foundational principles of museum institutions have undergone critical scrutiny and this has led to a crisis of purpose. Museums were formed in the time of the Enlightenment (the 18th century), when the pursuit of knowledge was considered paramount. While there has always been some hostility towards the principles of this period a number of intellectual trends since the late 1960s have consolidated this critical view.

Through the intellectual trends of postmodernism, cultural theory and post-colonial theory, the traditional justifications of the museum have been questioned to the point of crisis. The pursuit of knowledge has come to be seen not as universal or objective but as an expression of European prejudice. Not everyone in the sector supports these ideas of course, but for a while the dissenters have been pushed aside by an influential group of activists.

The question of how human remains are researched and displayed has become a lightning rod for a wider debate over the purpose of the museum. I have spoken to many campaigners who see the issue of repatriating or repositioning human remains – once considered scientific objects – as a way to signal a change of purpose for the institution. Removing them is a way of showing research is no longer a priority.

One of them explained that campaigning for repatriation and the removal of human remains from display was more important to him than his area of trained expertise. He told me: "I am an archaeologist. My specialism is the Persian period. A big find has just happened and I should go, I am the expert in this area, but I would much rather stay and do this. This is more pressing and important for me now."

This senior curator, and others like him, are taking it upon themselves to remove and hide the exhibits. In doing so they are also dismantling from within the purpose of the museum as an institution. The remit of research, learning from past peoples and the display important artefacts is under threat.

So, if you think that displays of human remains still have something valuable to teach us make sure that next time you go to a museum you ask them where they keep their skeletons – and tell them, where appropriate, to take them out of the closet.

Mummies: A history

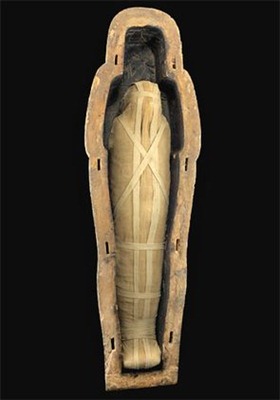

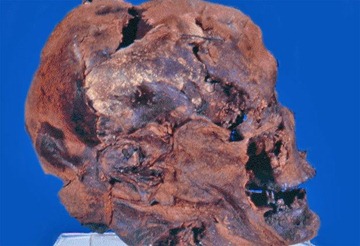

The word 'mummy' stems from the Persian word 'Mummiya', meaning 'bitumen', referring to the blackened state of the ancient Egyptian corpses. During mummification, the organs – including the skin – are preserved either intentionally or by natural means. Although mummies have been found all over the world the process is most commonly linked to Ancient Egypt.

Ancient Egyptian mummification was a ticket to the afterlife. The recently deceased's innards would be removed before the hollowed body was dried out with salts. The skin was then treated with oils, resins and perfumes and wrapped in linen for protection. The body would then be covered in charms and placed in a sarcophagus inside the tomb. The mummy was then buried with supplies of food, drink and any other comforts needed in the afterlife. Its mouth would be opened later to symbolise breathing and the continuation of life.

Author: Tiffany Jenkins | Source: The Independent/UK [February 16, 2011]