The Harvard Art Museums present Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia, on display in the museums’ Special Exhibitions Gallery from February 5 through September 18, 2016.

Aboriginal Artists Agency]

“The central idea of the exhibition is time,” said Gilchrist, the Australian Studies Visiting Curator at the Harvard Art Museums and associate lecturer in art history at the University of Sydney, Australia. “Everyone can relate to time; artists across the globe and across centuries have responded to the task of thinking about time and its promise, presentness, and passing. But this exhibition asks people to think about time from an Indigenous perspective, to consider how it is marked, observed, and sensed.”

While Indigenous art has at times been viewed by the international community as a relic of the past, the exhibition argues that Indigenous art and culture is equally invested in the past, present, and future. The exhibition asks visitors to consider Indigenous art as sophisticated, contemporary, and “of our time.” The exhibition also asks visitors to explore the underlying issues and experiences of the artists. While art has served as a customary medium for Indigenous people to pass on cultural practices, it has also provided a crucial public platform for Indigenous people. Through their works, Indigenous artists visualize ancient narratives, and also their experiences with colonial oppression, philosophies of ecological sustainability, interventions within museum collections, and the necessity of engaged political activism.

The exhibition features more than 70 works of varying scale and media, with the majority produced over the past 40 years. Drawn from public and private collections in Australia and the United States, many of the works have never been seen outside Australia. The exhibition is organized around four interrelated themes—Seasonality, Transformation, Performance, and Remembrance—all of which are central to Indigenous art and culture.

“Everywhen asks important and nuanced questions about the agency of contemporary Indigenous artists and how their works are situated within today’s global society,” said Deborah Martin Kao, the Landon and Lavinia Clay Chief Curator and interim co-director of the Harvard Art Museums.

In addition to the extraordinary works of contemporary art, which are realized in a wide array of media, from paintings on bark to video, the exhibition also makes a place for historical objects from Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The inclusion of these customary objects, such as coolamons (multipurpose carrying vessels, sometimes used to cradle babies), baskets for food gathering, and larrakitj (hollow log coffins), is to demonstrate how a life is lived, measured and made meaningful through cultural objects. While the names of the makers of these objects were rarely recorded by collectors, they nonetheless possess the tangible, human residue of their makers. The exhibition invites audiences to consider the histories of erasure in past museum displays and collecting practices that have marginalized, silenced, and dehumanized Indigenous people. The exhibition also speaks to the new politics of display that are symbolically reuniting objects to their source communities where possible.

“By including these objects, we are also trying to break down the divisions between art history and anthropology,” said Gilchrist. “For Indigenous people, art and culture are both software and hardware; they need to be seen and understood together.”

Works on Display

Approximately 10 to 15 works of art are showcased in each of the four thematic sections that make up the exhibition.

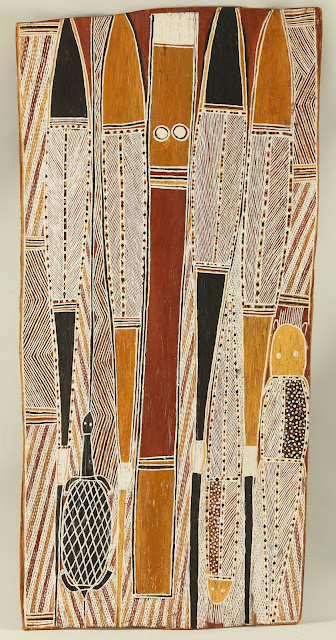

Transformation: The narratives told and retold by Indigenous people explain the origins of the natural world and often feature the travels of shape-shifting ancestors who metamorphosed into features of the landscape, vesting them with their sacred power. Indigenous artists create and re-create these narratives, and the sacred and significant sites associated with them, to canonize their spiritual ancestors and to re-energize their personal and cultural connection to them. The theme of transformation also applies more broadly to Indigenous art and culture, which is reimagined and reconstituted by those who create and live it. While many people erroneously associate Indigenous art and culture as being about the past, the works in this section emphasize that Indigenous people have always and continue to embrace adaptive and innovative practices. Works on display include Tommy Watson’s (born c. 1932) painting Wipu Rockhole (2004); Ronnie Tjampitjinpa’s (born c. 1932) Two Women Dreaming (1990); and Manydjarri Ganambarr’s (born c. 1952) poetic bark painting Djambarrpuyngu märna (1996).

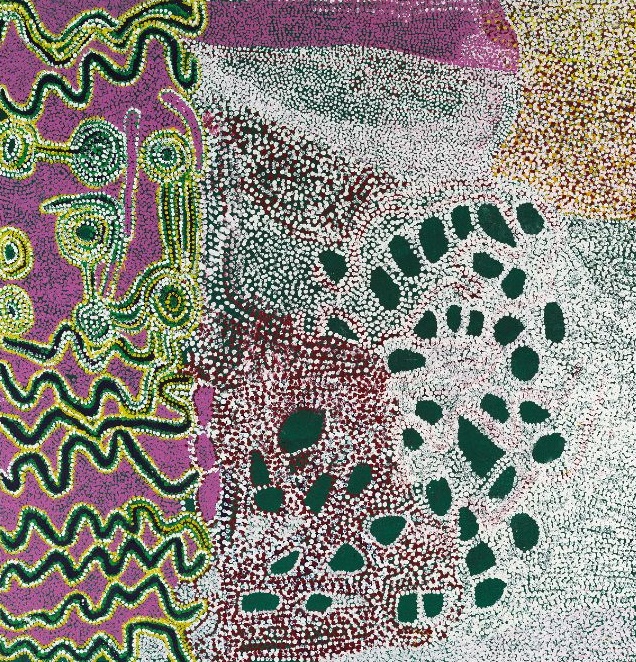

Performance: The ceremonies that Indigenous people attend and participate in are used by some Indigenous artists as the source iconography in their art. While Indigenous people continue to face ongoing challenges relating to the maintenance of cultural practice, ceremonial practices are often invoked in part by artists in the creation of their art. In a sense, art making has become a new medium of performance and the rhythm of ceremony resonates in sculptures, painted objects, and photographs. Works on display in this section include Doreen Reid Nakamarra’s (c. 1955–2009) large painting Untitled (2007), composed of thousands of small dots evoking the innumerable grains of sand that make up her desert country, as well as the rhythm and mindfulness of ceremonial performance; The Burala Rite (1972), a bark painting by Tom Djawa (1905–1980); and two woven baskets on loan from Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

Remembrance: Creating works of art that resonate with cultural memory, the artists in this section critically reflect on history and how it configures the present. The works invite visitors to consider what we choose to remember and what, and who, we are forced to forget. Serving the exhibition’s interest in the multilayered concept of the Everywhen, these works of art highlight how we carry the past within. Through artistic excursions into the past, personal memories, national histories, and practices captured in the collections of museums can be confronted, interrogated, and sometimes laid to rest. Works on display include Vernon Ah Kee’s (b. 1967) many lies (2004), a text-based vinyl work applied directly to the gallery wall; Julie Gough’s (b. 1965) Dark Valley, Van Diemen’s Land (2008), a “necklace” that hangs in the shape of Tasmania and is composed of Tasmanian coal; and three photographs from Christian Thompson’s (b. 1978) We Bury Our Own series from 2012, his response to the Australian photographic collection at the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

[Credit: © Emily Kam Kngwarray]

Conservation Research

As part of the research and preparation for the exhibition, conservation scientists in the Harvard Art Museums’ Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies launched the first ever large-scale technical examination of Indigenous Australian bark paintings, including historic objects that served as short-term shelters in wet weather. It was commonly thought that Indigenous artists would not have used binders, but after three years, two hundred samples, and analysis of fifty paintings, there is scientific evidence to challenge that view. The team found the first conclusive evidence that orchid juice was used as a binder in two of the oldest known bark paintings, dating to the late 19th century.

“For the first time, we are able to provide physical evidence to support or challenge theories from the past about the type and presence of binders in bark paintings,” said Australian Narayan Khandekar, senior conservation scientist and director of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies.

Khandekar and his team also uncovered more information about where Indigenous artists sourced their pigments. Traditional bark painting from Arnhem Land in the far north of Australia uses only four colors—yellow, white, red, and black—derived primarily from minerals. The team analyzed and mapped the elemental composition of pigments from historic bark paintings and then compared those pigments to ochres (earthen pigments) that the team had collected while visiting Indigenous art centers in Australia and conducting artist interviews. These findings will be added to an informal “atlas” of all Australian pigment sources, contributing to a greater understanding of the extensive ochre trade among Indigenous Australians. On Groote Eylandt, an area with abundant manganese deposits, they found that the artists used naturally occurring black as well as black from dry cell batteries and from charcoal, indicating a nuanced choice of material.

Source: The Harvard Art Museums [February 17, 2016]