coast of Anzac Cove, Gallipoli in 1998 [Credit: markspencer.com.au]

It is being called on to ratify the UN Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage in the lead-up to the centenary of World War I.

Australia played a leading role in drafting the convention adopted in 2001, but 13 years later it still has not signed it.

That is alarming to maritime archaeologists, including those who have been working to protect Anzac heritage off Gallipoli.

According to Tim Smith, who led the first systematic archaeological surveys of Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay, the sites are rich in heritage value.

"What survives underwater is potentially quite different to what survives on the land part of the battlefield."

He and his team discovered the wrecks of warships and landing barges, along with the ruins of jetties and bridging pontoons built by the Anzacs.

There were also bullet casings, shrapnel pellets and more remnants below the sand.

"You have the large shipwrecks, but you also have a lot of the remains of the war that were dumped into the sea during the conflict ... small items, small artefacts that really tell such an important part of the men's lives ashore," Mr Smith said.

"They're such evocative items, they really connect the people, the story and the place together."

Issue becoming a concern closer to home

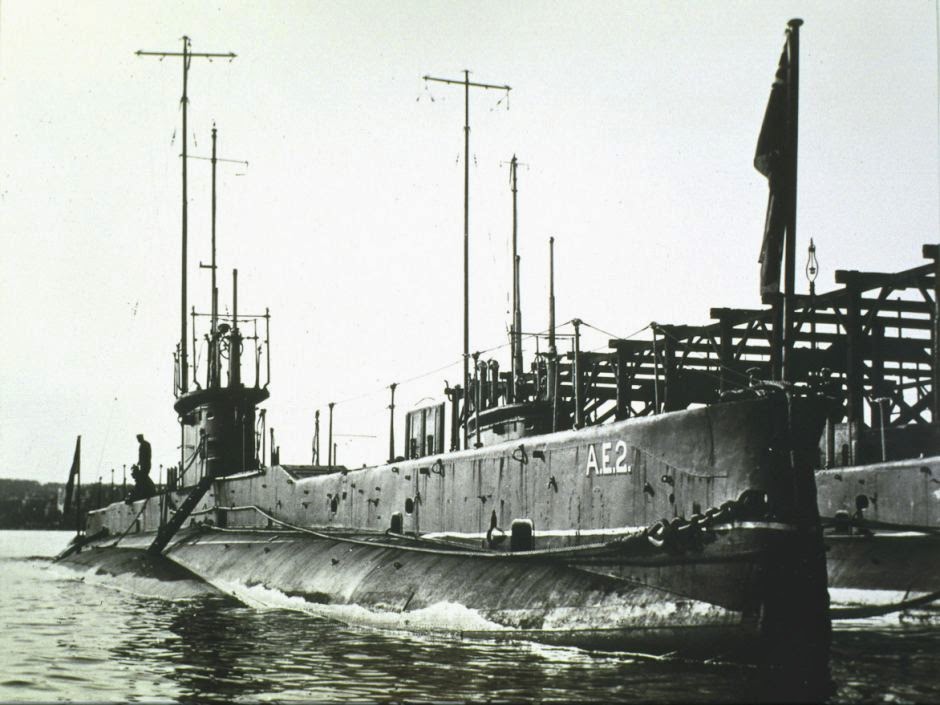

One of Australia's first submarines, the AE2, also lies off the Turkish coast.

the coast of Gallipoli in 1998 [Credit: markspencer.com.au]

Mr Smith said the Turkish government had been very protective of the underwater heritage around the Dardanelles battlefields, regarding it as sacred in the same way Australia does.

But that has not stopped souveniring at the sites over the past 100 years.

Given the rich underwater heritage, Mr Smith is concerned that neither Turkey nor Australia has signed the 2001 convention.

"All of this material under the water is part of the world's heritage, it's not just one nation's, so the convention will aid in presenting and promoting this heritage as part of all of our story, all of our shared history," he said.

"It's so important that all of the countries unite and help to protect and preserve and tell these amazing stories through the surviving artefacts beneath the sea."

in Sydney in 1914 [Credit: Tim Smith]

The issue is also becoming urgent closer to home, where World War II wrecks are being stripped and broken up by commercial salvagers.

They include HMAS Perth, to the horror of survivors of the ship's sinking by the Japanese off Indonesia in 1942.

Scuba divers have made official reports of large-scale damage to the wreck.

There is also concern about the Japanese ship Montevideo Maru, the gravesite of around 1,000 military and civilian prisoners of war, most of them Australian.

In addition, Australia's first submarine, the AE1, still lies undiscovered off Papua New Guinea, where it was lost at sea with all hands in 1914.

Asia-Pacific remains largely unprotected

While the Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage has now been ratified by 45 countries, the Asia-Pacific remains largely unprotected.

campaign in Gallipoli, Turkey [Credit: Tim Smith]

"Of those 45 countries, not a single one is in the Pacific Ocean and there's very little in the whole region of Australia, the Asian region," said maritime archaeologist Graeme Henderson.

Mr Henderson discovered the wreck of the Dutch East India Company's Vergulde Draeck (Gilded Dragon) off the West Australian coast when he was 16, only to see it blasted apart and looted.

So in the 1970s, he and others successfully lobbied the Australian government to introduce the world's first legislation protecting historic shipwrecks within our own waters.

Those standards were used to draft UNESCO's 2001 convention, which also covered sunken aircraft, antiquities, underwater cities and even traditional fish traps.

"Oh it's frustrating and ironic at the same time, because Australians had a great deal to do with the legislation and indeed Australia was a pioneer in terms of appropriate responsible management of underwater cultural heritage," Mr Henderson said.

"So we should be playing a lead role in the whole region, as one of those who have ratified."

Expert says there is no excuse for delaying action

Also frustrated about the lack of protection for WWI and WWII wrecks and remnants is international Cultural Heritage Law expert, Lyndel Prott.

of Gallipoli, Turkey in 1998 [Credit: markspencer.com.au]

"This is of great importance to Australia and also of course to Britain and many other countries that had substantial navies - a great many ships were lost during this period."

As director of UNESCO's Division of Cultural Heritage in 2001, Ms Prott oversaw the adoption of the convention.

More than a decade later, she believes there is no excuse for Australia's delay.

"I can't understand it because the states have all been consulted, the necessary departments in Canberra have all been consulted, and they have all agreed that it should go ahead and should be ratified," she said.

An intergovernmental agreement has been signed between the Commonwealth, states and territories defining their roles and responsibilities if the convention is ratified.

Enabling legislation still needs to be approved, then the final decision to go ahead will be up to the Environment Minister, Greg Hunt, who is himself a scuba diver.

Mr Henderson believes ratifying the 2001 convention would encourage the protection of Australian heritage outside our waters.

"I firmly believe that when Australia does ratify it, a lot of countries within this region will follow our lead," Mr Henderson said.

"The sites need protection in the same way as anything to do with our identity, our culture, our history, our heritage.

"If you don't have a history you're a lesser nation, if you don't have a culture you're a lesser nation - all these things add to knowledge and they add to our sense of who we are."

Author: Deborah Rice | Source: ABC News Website [March 21, 2014]