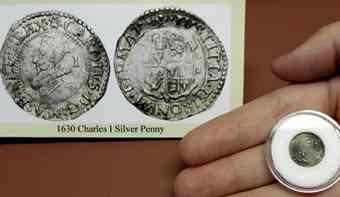

It’s tiny, made of silver and the man who had it minted lost his head for treason.

A unique English coin – a small, Charles I silver penny – is currently on display as part of a fascinating exhibit of coins found during excavations undertaken at Colonial Pemaquid State Historic Site in Bristol.

The small coin, dated 1630, is one of nine coins and a jetton, or counting piece, now being shown at the Colonial Pemaquid Museum, which also houses numerous artifacts found at the early colonial site. It is the oldest coin currently on display.

The small coin, dated 1630, is one of nine coins and a jetton, or counting piece, now being shown at the Colonial Pemaquid Museum, which also houses numerous artifacts found at the early colonial site. It is the oldest coin currently on display.

Two years in preparation, the coin exhibit that includes just English or colonial tokens shows the sophistication of the trade taking place at the seasonal fishing village, which was established by England in 1607 for the production of salted cod, according to park staff.

“These coins are wonderful because they tell us time [by the dates on them],” said Kate Raymond, a Colonial Pemaquid staffer who did much of the research for the exhibit. “They tell us about these people, and they tell us they used coins and didn’t just barter.”

"It is a chance to look into the past and see some coins you can’t see anywhere else,” Kelsie Tardif, Colonial Pemaquid manager, said of the exhibit. “Some of the most interesting artifacts we have are the old coins. Coin collectors who come here are excited to see them; they’re very rare, very old and in very good shape.”

Colonial Pemaquid State Historic Site, under the management of the Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands, is the location of one of New England’s earliest European settlements, rivaling Jamestown, Va.

The site originally was used as a seasonal settlement, if not year-round, by American Indians and later was colonized as a fishing station and then as a village in the 17th century. Three forts were built at the site starting in 1677, and English soldiers were garrisoned there. The property later became a family farm.

Located on the scenic Maine coast, the state historic site now has numerous archaeological sites and building foundations: Fort William Henry, a reconstructed 17th century fort; the federal-style Fort House, built in the 18th century and restored as a 19th century farm house; and the museum, which displays artifacts, maps, and a diorama of Colonial Pemaquid.

The new coin exhibit is based on a previous exhibit at the museum, but has been expanded with additional information and a number of coins never before displayed, Tardif said. The coins are all 17th and 18th century items that were found in the village area of Colonial Pemaquid and would have been used by villagers and in trade with the French.

Some coins also were found in the Fort William Henry area and would have been used as exchange by the officers billeted there, the park manager said.

The coins were all found between 1965-74 by Helen Camp, the self-taught archaeologist who explored Colonial Pemaquid, and her crew, Raymond said. The exhibit represents some but not all the coins found. “We have about 10 to 20 that we haven’t displayed,” she said.

Once kept in card stock, the coins have been placed in air-tight plastic sleeves for display and are much better preserved, though they definitely have not been cleaned.

“With coins, the details are so fine that if we get rid of the oxidation, we lose the details,” Raymond explained.

The tiny silver penny — “about the size of the tip of your pinkie” — is so small because it is made of silver. “For English coinage, the worth is the actual value of the metal,” Raymond said. “Silver was valued higher than copper or bronze.”

The penny was produced at the Tower of London and bears a bust of the king facing left with a I behind the head to denote the denomination of one penny, with the inscription CAROLUS D G MA B F ET HI REX (Charles by the grace of God King of Great Britain, France and Ireland), while the reverse shows an oval shield and the inscription IUSTITIA THRONUM FIRMAT (Justice strengthens the throne).

As a result of his opposition to the authority of the British Parliament and the English Civil War, Charles I was captured, convicted of treason, and executed in 1649 after a tumultuous monarchy.

Another fascinating coin in the exhibit is the Massachusetts Pine Tree Coin, a copper six-pence dated 1652 and made in Massachusetts. In fact the coin probably was struck later (1667-1682), but was dated earlier to make it look as if the makers were complying with English law that had limited the production of coins to the crown, Raymond said.

The coin is relatively rare, though “there is a handful around, but there aren’t many,” Raymond said, with other coins found in Massachusetts and other New England colonies. The coin was circulated widely in North America and the Caribbean, and the image of the pine may symbolize how important the pine tree was for export as ships’ masts. Other images used later on the coin were oak and willow trees on shilling pieces.

Perhaps the most unusual piece in the exhibit isn’t a coin at all, but is an English jetton, or counting piece, from the Queen Anne period, c. 1702-1714. The token most likely was made in Nuremburg, Germany, and the metal is copper.

“The only other one found that we know of was found in the toe of a boot in the Thames River [in England]," Raymond said. “No other has been found in the Americas; they are a rare find, and we have one.”

The jetton, which features a degraded profile of the queen on one side and design on the other, was used as a counting piece for accounting purposes. The jettons were used as counters with a grid of boxes representing one, tens, hundreds, etc., as a type of abacus, Raymond explained. The counting system has been found described in old documents, she said.

The front exhibit room of the Colonial Pemaquid museum has undergone recent renovations, with other new items on display, Raymond said. There also are plans for rotating the exhibits in the rest of the museum, so it’s always worth a return visit. Tours are available on weekends for the general public, while tours for school groups can be arranged through the park manager.

“We have about one thousand artifacts in the museum now, and there are about 100,000 artifacts in the whole collection,” Raymond said. “And we find more every time we dig.”

Another dig at the site is scheduled for the second week of August by the Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

Source: Capital weekly [June 28, 2010]