I've made a grave mistake, I think, sitting rigid in the clap-trap kombi approaching Montségur in southern France. The hills are as steep as the dales are deep, and the vehicle's integrity rests entirely on duct tape.

For a week, I'd been happily camped on the Atlantic coast just south of Bordeaux, content with playing boules and eating moules marinière, when a ragged troupe of fellow South Africans blunted my wits with their high and generous devotion to the herb, and invited me to join them on their quest into Cathar Country, or Pays Cathare, as the French call it.

For a week, I'd been happily camped on the Atlantic coast just south of Bordeaux, content with playing boules and eating moules marinière, when a ragged troupe of fellow South Africans blunted my wits with their high and generous devotion to the herb, and invited me to join them on their quest into Cathar Country, or Pays Cathare, as the French call it.

As the VW veers along the precarious passes, I finally recognise the driver as one of the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers.

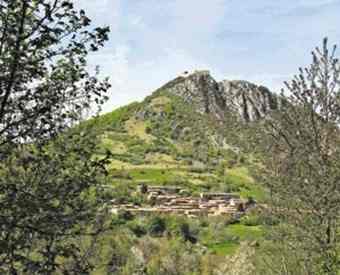

Amazingly, we survive to reach Montségur. The engine splutters to a halt and we decant into a parking lot at the foot of a towering peak, crowned with a castle ruin. It's an awesome spectacle, and the steep climb is intimidating. I am surrounded by verdant hills and a sunny, tourist-friendly atmosphere that belies the history of the place.

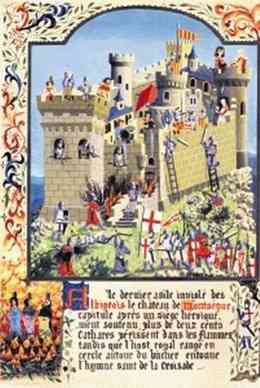

Where I stand, among the Renaults and Citroëns, more than 200 people were burned en masse about 800 years ago. The grim bonfire in 1244 marked the end of a brutal 10-month siege that sealed the fate of the last Cathars. Catharism had been a populist religion whose adherents included a sizable portion of the population of Languedoc, among them many noble families and courts. They also lived in concentrations in Germany, northern France and northern Italy.

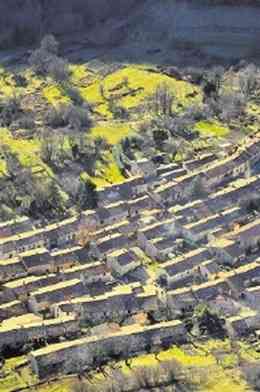

My companions lead the way and we are soon under a canopy of leaves. I muse at how lentil heads and their ilk are so attracted to the Cathars. The present company's ramblings are littered with references to Cathar prophecy and the ruin's solar-alignment characteristics, said to be visible at dawn on the summer solstice. These dubious theories are popular, but what they overlook is that the present fortress at Montségur is not from the Cathar era - only the small ruins of the terraced dwellings, immediately outside the current fortress walls, are confirmed to be authentic former Cathar habitations.

My companions lead the way and we are soon under a canopy of leaves. I muse at how lentil heads and their ilk are so attracted to the Cathars. The present company's ramblings are littered with references to Cathar prophecy and the ruin's solar-alignment characteristics, said to be visible at dawn on the summer solstice. These dubious theories are popular, but what they overlook is that the present fortress at Montségur is not from the Cathar era - only the small ruins of the terraced dwellings, immediately outside the current fortress walls, are confirmed to be authentic former Cathar habitations.

This is something the French tourist authority underplays, for which they've drawn some criticism. Not that it matters. Once you reach the top (after about 45 minutes) and see the Pyrenees in the distance, the place proves to be one of the most special destinations in France - provided you have the benefit of some historical background. It should not matter that the present ruin was rebuilt by the royal forces that razed the original Cathar castle after its capture. The breathtaking setting still conveys a powerful feeling for the dramatic last stand of the Cathars.

Much of the fringe interest in Montségur stems from the popular legend that, just days before the fall of the fortress, a small band of believers managed to slip through the besiegers' lines in the dead of night, carrying a mysterious treasure with them. The brochures in the village nearby all refer to this. The nature and fate of this treasure has never been established, although speculation has focused on the Holy Grail.

This is not surprising, since many scholars have nominated Montségur as the Holy Grail castle. In Wolfram von Eschenbach's epic poem Parzival (circa 1200-1210), the linguistic correlations are intriguing. His Grail castle is called Monsalvat, which is similar to Montségur and has the same meaning: "safe mountain". The book Crusade Against the Grail by Otto Rahn in the 1930s did much to rekindle interest in the connection between Catharism and the Holy Grail, and painted Parzival as a veiled account of the Cathars. Rahn's research attracted the attention of Heinrich Himmler, who made him an archaeologist in the SS (which, in turn, is thought to have inspired one of the characters in Raiders of the Lost Ark).

This is not surprising, since many scholars have nominated Montségur as the Holy Grail castle. In Wolfram von Eschenbach's epic poem Parzival (circa 1200-1210), the linguistic correlations are intriguing. His Grail castle is called Monsalvat, which is similar to Montségur and has the same meaning: "safe mountain". The book Crusade Against the Grail by Otto Rahn in the 1930s did much to rekindle interest in the connection between Catharism and the Holy Grail, and painted Parzival as a veiled account of the Cathars. Rahn's research attracted the attention of Heinrich Himmler, who made him an archaeologist in the SS (which, in turn, is thought to have inspired one of the characters in Raiders of the Lost Ark).

But what was it about this religion that saw the Catholic Church launch a 20-year war of extermination? The answers to this also explain the interest from today's more alternative-minded. For one, the Cathars rejected the most fearful dogmas of Catholicism: hell and purgatory. Instead, they believed in reincarnation, which is but one aspect that would win them the label of "Western Buddhists" in Zoé Oldenbourg's classic, Massacre at Montségur. They believed the Christian doctrine of resurrection did not refer to the physical raising of a dead body from the grave, but to something far more Vedic.

The Cathars believed that each human carries a spark of divine light that is obscured by incarnation in a physical body. To them, this world was created by a lesser deity, similar to what the Gnostics called the Demiurge. Humanity is trapped in a polluted world created by a usurper God and ruled by his corrupt minions.

The path to liberation first required an awakening to the intrinsic corruption of the medieval "consensus reality", including its ecclesiastical, dogmatic and social structures.

The path to liberation first required an awakening to the intrinsic corruption of the medieval "consensus reality", including its ecclesiastical, dogmatic and social structures.

The Cathars held the conviction that love and power were completely incompatible, and strongly rejected all forms of war - an unusual stance in medieval times.

And their hippie ethos doesn't end there. Informal relationships were preferred among Cathars, and they rejected marriage vows. When called before the Inquisition, one accused of Catharism needed only to show that he was married for the case to be dismissed.

They also claimed an Apostolic succession from the founders of Christianity, and saw Rome as having betrayed the original purity of the message. No wonder the Catholic Church considered the movement dangerously heretical.

Pope Innocent III placed the crusader army under the command of an abbot called Arnaud-Amaury. In the first serious engagement of the war, the town of Béziers was besieged in 1209. Its Catholic inhabitants were granted the freedom to leave unharmed, but many chose to fight alongside the Cathars.

Arnaud was famously asked how to distinguish Cathars from Catholics. His reply: "Kill them all, the Lord will recognise His own."

The doors of the church of St Mary Magdalene were broken down and 7000 refugees, including women and children, were slaughtered. Elsewhere in the town, many more thousands were killed or tortured. Many were blinded, dragged behind horses, or used for target practice. What remained of the city was razed by fire. Arnaud wrote to the Pope: "Today, your Holiness, 20,000 heretics were put to the sword."

Today, most of our knowledge of the Cathars is derived from their opponents, their original writings having been destroyed by order of the Papacy. Consequently, we have only a partial view of their beliefs. Cathar ideology continues to be debated, with academics often accusing their opponents of speculation or distortion.

Today, most of our knowledge of the Cathars is derived from their opponents, their original writings having been destroyed by order of the Papacy. Consequently, we have only a partial view of their beliefs. Cathar ideology continues to be debated, with academics often accusing their opponents of speculation or distortion.

I've been crawling around the ramparts for hours, and standing on the platforms from which tourists are afforded the most sublime views of the surrounding countryside. But now the sun has set and a sudden hush descends.

The few tourists who are left, my companions included, all fall silent, and we stare at each other knowingly - we're sharing a moment.

For a long time, everyone stops and listens. The place is pregnant with something ineffable. Perhaps it is a nostalgia for what never was, and a world in which the Cathars are still among us.

Source: Times LIVE