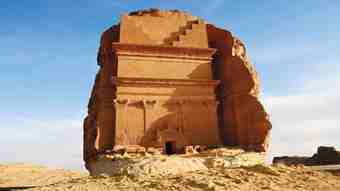

Al-Hijr, whose ancient Nabatean name is Hegra, is the best known of the archaeological sites in Saudi Arabia. Otherwise known as Madain Saleh, the site has been the focus of attention for archaeologists over the last decade or so, not only because of the magnificent tombs and other monuments carved in the sandstone outcrops by the Nabateans, but also because of the wild desolate landscape in which it stands.

Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Madain Saleh will inevitably attract increasing numbers of visitors over the next few years. The construction of a new airport under way near Al-Ula, the nearest town to the site, indicates a drive to develop the region.

Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Madain Saleh will inevitably attract increasing numbers of visitors over the next few years. The construction of a new airport under way near Al-Ula, the nearest town to the site, indicates a drive to develop the region.

Archaeology and tourism rarely mix. The rock-cut monuments are very fragile and it is vital that drastic measures are taken to protect the site against the detrimental effects of mass tourism.

The Supreme Commission for Tourism and Antiquities has accounted for this threat in their management plan that is being prepared by its offices in Riyadh.

Hardly a resort, the attraction of Madain Saleh lies not in what it is, but in what it was. That alone should filter the visitors and yield responsible tourists in the academic and well-informed amateur bracket, particularly the “gray dollar” band of foreign retirees with disposable incomes.

Al-Hijr, the Arabic name, occurs in a variety of Arabic sources and in the Quran. It is still in use today by the local people, whereas the name Madain Saleh, which is more usual among foreign visitors and archaeologists, was given to the site in the 17th century.

As with any conurbation, modern or ancient, the geographical location is frequently an important key to understanding the social history of a site.

The archaeological site of Madain Saleh is located 20 km north of the Al-Ula town, 400 km northwest of Madinah and 500km southeast of Petra, the Nabatean capital in modern-day Jordan.

The physical geography of the Madain Saleh site is important. It lies in a relatively flat sandy basin, which 2,000 years ago was a substantial aquifer. Although the water levels have dropped from an estimated few meters below the surface to more than 20 meters today, it was sufficiently bountiful at the time to support a major city and its agricultural infrastructure.

The aquifers are fed by the run-off water from the nearby huge Harrat Al-‘Uwayrid. Although the area receives less than 100mm of rain a year, the impervious volcanic harrat (a flattish layer of volcanically extruded lava, mainly basalt) is a relatively efficient catchment area and transporter of water into the aquifer.

The water was withdrawn from two large wells within the city walls — their remains can be seen today — and perhaps 120 smaller wells.

The Nabatean farmers capitalized on the carving and construction skills of the culture for they built canals and stone pipes to transport water to their crops.

The area was relatively fertile for as well as dates, which sustained both the local inhabitants and the passing caravan traders, research indicates that they also grew some varieties of wheat.

It takes around 750 liters of water to produce one kilogram of maize and between 1,000 and 1,350 liters for wheat — so it seems that the aquifer was both bountiful and reliable. It surely figures as a main reason for the location of the site.

It takes around 750 liters of water to produce one kilogram of maize and between 1,000 and 1,350 liters for wheat — so it seems that the aquifer was both bountiful and reliable. It surely figures as a main reason for the location of the site.

The tombs themselves suggest there was considerable wealth in Madain Saleh.

Although Madain Saleh is best known for its magnificent tombs, the inhabitants of the city lived in somewhat humbler circumstances. Then as now, money talks and drives the tendency to show off with conspicuous consumption. Fortunately for posterity the tombs were the designer labels of the day, but a great deal more lasting.

Within the 140 hectare trapezoid shaped city wall, lies the residential housing. Most of it was constructed from mud bricks — very similar to those seen in the crumbling ruins of villages in the wadi a few kilometers south of the site. Again, water was a key element in the foundation and construction of the city.

Some of the grander houses were stone built — more lasting and occasionally visible as low remains. What is certain is that the city was densely populated with a bustling civic life. Houses sharing walls indicate that space was at a premium, while remains of pillars, stone basins and basalt millstones indicate a combination of grandeur and practicality.

Apart from the rock-cut tombs, the Nabateans were great experts in the making of pottery. The plates and bowls, decorated with plants or geometric designs and produced in their workshops, mainly in Petra, are finely made and recall later egg-shell pottery.

They also liked terracotta figurines with which they represented divine, human or animal figures such as camels. Skilled sculptors fulfilled private or public commissions.

The abundance of water and fertile soil might in part account for the location of the city, but there was clearly wealth as well.

Prodigious expenditure of time and income, most importantly disposable income at private and civic level, in the form of spectacular tombs carved in the local sandstone outcroppings, indicate that there was a workforce not fully engaged in agriculture and the vicissitudes of daily survival.

Perhaps there was a separate artisan class paid to construct the famous tombs. Their tools were crude — mainly chisels and mallets — and to produce monumental sculptures using hand tools takes both time and a great deal of labor as well as money, lots of it.

The wealth of Madain Saleh came from the incense route and the trade and taxes that came from it. Well positioned to intercept the south-north route from Yemen to the Mediterranean empires and the East-West route that passed through Al-Jouf, the city thrived.

Well established since Solomonic times, the trade sustained the city for centuries, only declining when the unceasing attention of brigands drove trade onto shipping routes on the Red Sea.

Nabataea reached the peak of its prosperity under King Aretas IV (9 BC — 40 AD). He built its far-flung settlements along the caravan routes to develop the prosperous incense trade.

During his reign, the theater in Petra was carved and Qasr El-Bint temple (also in Petra) was erected. The king placed importance on agriculture and rainwater storage. In general, the Nabateans were great water engineers and irrigated their land with ingenious systems of dams and canals, essential to the survival of Madain Saleh.

The last Nabatean king was Rabel II who died in 106 AD. After his death, the Nabatean kingdom was controlled by the Romans and was known as Provincia Arabia. What remains is very worthy of attention.

The spectacular tombs for which the site is famous are positioned around the urban area, often at some distance. Most have their facades facing the city, probably in the interests of continuously announcing the importance of the owner.

The showy tombs were meant to be seen and expressed the wealth, power and prestige of the family. They were therefore very visible, despite the distance that separates the areas where tombs were carved — the necropolis — from the residential area.

The plain is scattered with sandstone outcrops, the highest of which, Jabal Ithlib, is in the northeast part of the site. It is in this area that the pre-Islamic Nabateans hid the sanctuaries of their gods such as Dûshara, Shay‘alqawm or Al-‘Uzza, along with several others.

There are between 94 and 131 tombs on site, depending on whether you define a tomb as a simple hole in the rock or a spectacular monument.

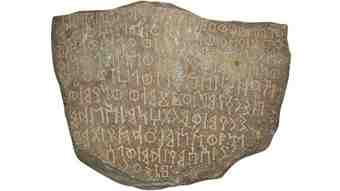

Many exhibit a decorated façade and a funerary chamber at the back. Topped with single or double rows of characteristically Assyrian and Nabatean “crowsteps” (blocky rising-step decorations, usually five steps in all) or just two large half crowsteps, the lower part of the façade is sometimes flanked by pilasters topped with Nabatean capitals, while the lower middle part was pierced with a decorated framed door. The worshippers who entered the Jabal Ithlib to participate in religious ceremonies often carved their name along with their father’s name in the rock faces next to the sanctuaries.

Many exhibit a decorated façade and a funerary chamber at the back. Topped with single or double rows of characteristically Assyrian and Nabatean “crowsteps” (blocky rising-step decorations, usually five steps in all) or just two large half crowsteps, the lower part of the façade is sometimes flanked by pilasters topped with Nabatean capitals, while the lower middle part was pierced with a decorated framed door. The worshippers who entered the Jabal Ithlib to participate in religious ceremonies often carved their name along with their father’s name in the rock faces next to the sanctuaries.

The inscriptions make up a list of people who visited the site two millennia ago, but they are also a key to unlocking Nabatean writings and revealing the source of modern Arabic. The contribution of Madain Saleh to understanding the origins of Arabic script is one of the less well known results of the archaeological investigations carried out there.

A further source of writing can be found on the monumental family tombs that characterize the site. Nabatean inscriptions are carved on the façade of 33 of them.

These inscriptions, among the longest texts known in Nabatean epigraphy, date back to between 1 AD and 75 AD and have been thoroughly studied since the French scholars A. Jaussen and R. Savignac recorded them.

These inscriptions are legal texts, copies of which were kept in one of the temples of the city. They say whoever made the tomb would list the people (wife, daughter or father) or groups of people (children or descendants) who would be buried in it.

The texts also list all actions that are forbidden, such as opening the tomb, selling it, removing a body from it or burying someone whose name is not mentioned in the inscription. This is followed by the amount of the fine that had to be paid by the violator to the king or the priest. Wrongdoers were also under the threat of a malediction from the gods.

Many bear distinctive decorative features such as sphinxes, human masks, rosettes, eagles or ribbed urns not found in the tombs of the Nabatean capital. Due to the denser quality of the sandstone and perhaps also to a reduced exposure to wind and erosion, some of them are better preserved than those in Petra.

Very often, it is possible to see clearly the traces left by the tools used by the ancient stonecutters on the rock. Behind the richly decorated façade, there is usually a very poor, sometimes even unfinished, funerary chamber, in which the deceased were buried.

It is likely that the owner of the tomb was buried in the most prestigious location of the tomb, in the middle of the back wall of the chamber while other members of the family were buried in other places, either in the walls or in rectangular pits dug in the floor of the chamber. Some burial places were obviously made for children because they are too small to have contained the body of an adult.

Then as now, the rich were separated from the poor in death as well as life. Their monumental tombs are for prestigious burials, made by and for the richest inhabitants of the cities.

The tombs’ size varies from less than three meters for the smallest to more than 20 meters for the largest. It is therefore very probable that only members of the middle or upper class could afford to carve a decorated façade for their family, while only governors or possibly members of the royal family could afford the very large tombs, such as Qasr As-Sani‘ or Qasr Al-Farîd.

The poorest inhabitants of the city had to be content with ordinary, human size pits carved on top of the outcrops, of which there are hundreds visible.

Ancient Hegra, modern Al-Hijr, Madain Saleh for tourists and visitors, is a fascinating site that has probably not delivered all its secrets. It awaits archaeologists, epigraphists, historians and specialists of other disciplines to penetrate the mysteries of its past to try to reconstruct all the aspects of its story.

Questions remain. Who lived there? For how long? What did their houses look like? How did they bury their dead? Were there a lot of foreigners? Who did they have contacts with?

All these questions are being answered by the members of the Saudi-French archaeological team who has set up a new exploratory project of the site, which started in early 2008 and is one of the first of this type in the Kingdom.

Cultural cooperation between institutions and people, of which the only aim is to increase knowledge, with no financial, political or strategic motives, is of great value and should definitely be encouraged.

Author: Roger Harrison | Source: Arab News [July 13, 2010]