Archaeologists and clerics here say they have unearthed bones belonging to John the Baptist, an itinerant preacher revered by many Christians as the last of the Old Testament prophets.

Bulgaria's government is looking to the discovery for salvation—of a financial sort.

Bulgaria's government is looking to the discovery for salvation—of a financial sort.

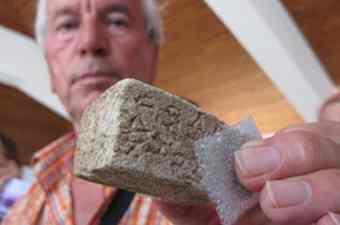

The remains, including a skull fragment and a tooth, were uncovered last month during the excavation of a fourth-century monastery on St. Ivan Island, off Bulgaria's Black Sea coast. They were in a sealed reliquary buried next to a tiny urn inscribed with St. John's name and his birth date.

Officials of this recession-scarred country think the purported relics will give a big boost to tourism, drawing believers from neighboring Orthodox Christian countries to this nearby resort town,

Tens of millions of dollars have already been earmarked to prepare for an anticipated surge in visitors. Construction crews are enlarging the port and building a big new parking lot. Tour guides are being rewritten and new signs are going up to direct people to the relics.

"I'm not religious but these relics are in the premier league," says Simeon Djankov, Bulgaria's finance minister and an avowed atheist. "The revenue potential for Bulgaria is clear."

Bulgaria's Orthodox church hierarchy has declared that the bones are authentic. "This is a holy find. It doesn't matter about the science," says Metropolitan Bishop Joanikii of Sliven, who oversees church affairs in Sozopol. "The holy relics of St. John radiate miraculous force. I cannot explain it by using words."

Kazimir Popkonstantinov, the archaeologist responsible for the finding in Sozopol and now hailed as a national hero, insists his discovery is in the same league as the Shroud of Turin. "This kind of discovery happens perhaps once every two hundred years," he says. "We have very strong proof that this is genuine. I know this is very important for the whole Christian world."

Some experts, however, are skeptical about the origin of the bones—as well as their earnings potential. Michael Hesemann, a religious historian who helps the Vatican date relics, says the bone fragments "appear to be authentic." But he thinks they lack the "box-office draw" of better-known religious attractions such as the Shroud, which believers say is Christ's burial cloth.

For its part, the Roman Catholic church says the matter requires more study. The Vatican's Pontifical Commission of Sacred Archaeology said tests to gauge the age of the bones and other factors would have to be weighed before it could judge their provenance.

News of the find, meanwhile, is already drawing visitors. At the local church of St. George, where the presumed relics are now on temporary display in a silver chest donated by Bulgaria's prime minister, hundreds of faithful line up for a chance to view the bones, mouthing prayers and making the sign of the cross.

The church says attendance at daily mass has jumped from about 100 to more than 3,000. Church officials say they are selling more votive candles in a day now than they used to sell in a year, and have just ordered another two tons of them to meet projected demand.

Bulgaria, the European Union's poorest nation, could use an economic miracle. The country's gross domestic product shrank 5% last year and contracted another 3.6% in the first three months of this year. Manufacturing has languished, and unemployment has climbed.

To help pull Bulgaria out of its worst recession since the collapse of communism here 20 years ago, the government is looking to promote tourism. Touting the relics is part of that plan. Mr. Djankov, the finance minister, says he wants to double government spending on the development of religious tourism so "we can make this history profitable."

Religious pilgrimages are big business globally, according to the World Tourism Organization, which estimates that up to 330 million faithful visit the world's key religious sites every year. Lourdes, the French town where worshippers believe the Virgin Mary appeared in 1858, draws about 5 million visitors annually.

The bones, though, make Bulgaria a member of a not-so-exclusive club of nations that say they are home to pieces of John the Baptist, who was beheaded on the orders of King Herod. Ancient tradition has held that his severed head was entombed in Herod's Jerusalem palace.

Over time, body parts believed to be St. John's have spread across Europe, the Middle East and South Asia. A church in Calcutta, India, claims to house part of a saintly hand.

The cathedral in Aachen, Germany, says it has the cloth used to wrap St. John's head after his decapitation. The Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, former seat of the Ottoman emperors, also claims to hold parts of one of St. John's arms and his head.

The presence of the relics of St. John hasn't translated into a tourist bonanza in any of these other resting places. Still, authorities in Bulgaria remain optimistic.

Orthodox Christians hold John the Baptist, who according to some accounts baptized Jesus, in especially high esteem. Services every Tuesday are dedicated to his memory in Orthodox churches.

There are some encouraging signs. Milenna Dimitrova, who has been selling fresh berries, figs and jams for 20 years from a stall here, says business has been so brisk that she doesn't have time to go to church. "The season was awful before—this is clearly a gift from God," she says.

Still, the hotel business in Sozopol continues to languish. Stanimir Stoyanov, a veteran hotelier who now runs the Hotel Duma, says occupancy is down by about a third since last year. "The government are telling us the town will become the next Jerusalem," he says. "We just hope that they're right."

Author: Joe Parkinson | Source: The Wall Street Journal [August 12, 2010]