The fragments of mosaic lie scattered in the dust like shiny white teeth, bleached by the tireless sun. Amid the lonely Roman ruins of Ptolemais, near Benghazi on the east coast of Libya, time has turned the graceful geometric patterns decorating the floor of a once-sumptuous residence into a 2,000-year-old jigsaw puzzle.

It is an arresting sight, and I’m sorely tempted to sit down and complete it, to restore some visual harmony before the mosaic’s zestful swirls become irretrievably scattered by sheep, storms and the tourists now finding their way to such poignant classical sites. I’m also moved to slip a few of these tiny, hand-tooled tesserae into my pocket as a souvenir of this thought-provoking encounter with the pixels of the past. Of course, both of these actions would be futile, sentimental gestures.

It is an arresting sight, and I’m sorely tempted to sit down and complete it, to restore some visual harmony before the mosaic’s zestful swirls become irretrievably scattered by sheep, storms and the tourists now finding their way to such poignant classical sites. I’m also moved to slip a few of these tiny, hand-tooled tesserae into my pocket as a souvenir of this thought-provoking encounter with the pixels of the past. Of course, both of these actions would be futile, sentimental gestures.

The disintegrating stone carpets of Ptolemais are just one of countless treasures left behind from the glory days of the Roman empire as it flourished on the southern shores of the Mediterranean between the first and fourth centuries. The legacy of this heyday is particularly rich in Libya, which has been attracting growing numbers of international travellers since 2003, when the UN lifted sanctions imposed after the Lockerbie bombing in 1988.

The disintegrating stone carpets of Ptolemais are just one of countless treasures left behind from the glory days of the Roman empire as it flourished on the southern shores of the Mediterranean between the first and fourth centuries. The legacy of this heyday is particularly rich in Libya, which has been attracting growing numbers of international travellers since 2003, when the UN lifted sanctions imposed after the Lockerbie bombing in 1988.

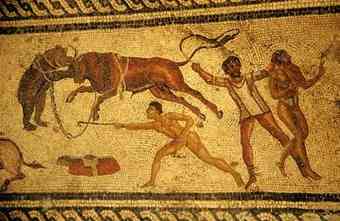

Rather than add to the ruination of this mosaic, which is a paltry example compared to the fabulous scenes of frolicking gods, gladiatorial combat and the villa good life that can be seen in the country’s archaeological museums, I know it is much better to simply savour this moment, and reflect on the privileges of modern travel that allow us to whizz around the world enjoying such reveries. And besides, Ali, our tour guide, is waving at me frantically. OK, OK ... Yes, I know there is so much more to see. The 6th-century basilica, the gymnasium, the cavernous cisterns – and it all has to be done before lunch at 1pm, because that’s what the itinerary says.

Rather than add to the ruination of this mosaic, which is a paltry example compared to the fabulous scenes of frolicking gods, gladiatorial combat and the villa good life that can be seen in the country’s archaeological museums, I know it is much better to simply savour this moment, and reflect on the privileges of modern travel that allow us to whizz around the world enjoying such reveries. And besides, Ali, our tour guide, is waving at me frantically. OK, OK ... Yes, I know there is so much more to see. The 6th-century basilica, the gymnasium, the cavernous cisterns – and it all has to be done before lunch at 1pm, because that’s what the itinerary says.

Travelling in a tour group is always a pact with the devil. You get to see so much, so easily, but at times things are frustratingly rushed and pre-determined. In the case of Libya, though, joining an organised tour makes sense. While independent travel is not impossible, official requirements, such as the need to get a visa and make at least some arrangements through a local travel agent, mean this is really only an option for the die-hard backpacker.

Travelling in a tour group is always a pact with the devil. You get to see so much, so easily, but at times things are frustratingly rushed and pre-determined. In the case of Libya, though, joining an organised tour makes sense. While independent travel is not impossible, official requirements, such as the need to get a visa and make at least some arrangements through a local travel agent, mean this is really only an option for the die-hard backpacker.

More importantly, it is crucial to have a good guide who can bring all these ancient temples, columned palaces and tiered amphitheatres to life – and that’s best achieved by booking through a company expert in cultural holidays. It is utterly dismaying, as I found on a recent fleeting visit by cruise ship, to be allotted a guide whose uselessness is matched only by his eagerness to crack jokes. “I only do this to practice my English,” admitted Fareed, who was moonlighting from his regular job as an immigration official.

More importantly, it is crucial to have a good guide who can bring all these ancient temples, columned palaces and tiered amphitheatres to life – and that’s best achieved by booking through a company expert in cultural holidays. It is utterly dismaying, as I found on a recent fleeting visit by cruise ship, to be allotted a guide whose uselessness is matched only by his eagerness to crack jokes. “I only do this to practice my English,” admitted Fareed, who was moonlighting from his regular job as an immigration official.

Fortunately, Libya is now receiving some serious attention from guidebook publishers, including a new series covering the archaeological sites by the London-based Society for Libyan Studies. Some tour groups travel with their own imported expert, usually a university lecturer with a passion for ancient Rome, and good local guides do exist. Touring Sabratha, 70km west of the capital, Tripoli, I was pleased to encounter the hard-working Tariq, who came armed with informative maps and photocopies and always had satisfying answers to the many questions fired at him.

Fortunately, Libya is now receiving some serious attention from guidebook publishers, including a new series covering the archaeological sites by the London-based Society for Libyan Studies. Some tour groups travel with their own imported expert, usually a university lecturer with a passion for ancient Rome, and good local guides do exist. Touring Sabratha, 70km west of the capital, Tripoli, I was pleased to encounter the hard-working Tariq, who came armed with informative maps and photocopies and always had satisfying answers to the many questions fired at him.

With its dream setting beside the sparkling Mediterranean, complete with wildflowers and birdsong, the Roman ruins here have a peace and beauty that quickly dispel any fear that visiting archaeological sites is always a hot, dry and dusty slog. The star attraction is a magnificently decorated 5,000-seat theatre – the largest in Roman Africa – that was restored in the 1930s when the country was under Italian occupation.

With its dream setting beside the sparkling Mediterranean, complete with wildflowers and birdsong, the Roman ruins here have a peace and beauty that quickly dispel any fear that visiting archaeological sites is always a hot, dry and dusty slog. The star attraction is a magnificently decorated 5,000-seat theatre – the largest in Roman Africa – that was restored in the 1930s when the country was under Italian occupation.

While Libya has much to offer us – including towering mud-brick Berber granaries, exceptional prehistoric rock art and wild adventures beneath the Saharan stars – its most powerful visitor magnet by far is Leptis Magna. A 75-minute drive west of Tripoli, this was the capital of Roman Africa in the third century. Earthquakes, floods and imperial decline led to its downfall, then the desert sands covered everything up until a group of Italian soldiers found themselves camping on top of the Arch of Septimus Severus in the 1920s.

While Libya has much to offer us – including towering mud-brick Berber granaries, exceptional prehistoric rock art and wild adventures beneath the Saharan stars – its most powerful visitor magnet by far is Leptis Magna. A 75-minute drive west of Tripoli, this was the capital of Roman Africa in the third century. Earthquakes, floods and imperial decline led to its downfall, then the desert sands covered everything up until a group of Italian soldiers found themselves camping on top of the Arch of Septimus Severus in the 1920s.

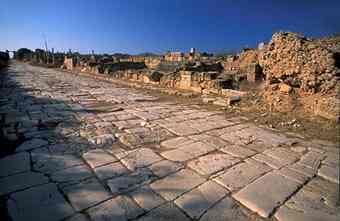

As ruins go, Leptis is world class on two counts. Firstly, it is huge. Here you can wander the streets of a prosperous seaside city that was once home to 100,000 people – and because Libya is still a relatively new arrival to the tourist map, at times it feels like you’ve got the whole place to yourself. Secondly, the quality of what survives is astounding – a haughty triumphal arch, a massive forum, lavish marble baths, a 16,000-seater amphitheatre, a seaside hippodrome where races were held before roaring crowds of up to 23,000 spectators.

As ruins go, Leptis is world class on two counts. Firstly, it is huge. Here you can wander the streets of a prosperous seaside city that was once home to 100,000 people – and because Libya is still a relatively new arrival to the tourist map, at times it feels like you’ve got the whole place to yourself. Secondly, the quality of what survives is astounding – a haughty triumphal arch, a massive forum, lavish marble baths, a 16,000-seater amphitheatre, a seaside hippodrome where races were held before roaring crowds of up to 23,000 spectators.

Visitors frequently remark, as they wander the flagstoned roads rutted with the wheel marks of bygone chariots, how easy it is to imagine people living here all those years ago. Bridging the gap between them and us, then and now, is easy when you visit the city market, with its marble fish counters and carved stone tables where oil and spices were measured out. The theatre still has its VIP box, road-signs point the way to the brothel, rows of marble latrines take us back to basics. In the nearby Villa Silin, a luxurious second-century des res, the walls and floors are decorated with delicate frescoes and exquisite mosaics depicting pygmies, crocodiles and chariots competing at the circus.

Visitors frequently remark, as they wander the flagstoned roads rutted with the wheel marks of bygone chariots, how easy it is to imagine people living here all those years ago. Bridging the gap between them and us, then and now, is easy when you visit the city market, with its marble fish counters and carved stone tables where oil and spices were measured out. The theatre still has its VIP box, road-signs point the way to the brothel, rows of marble latrines take us back to basics. In the nearby Villa Silin, a luxurious second-century des res, the walls and floors are decorated with delicate frescoes and exquisite mosaics depicting pygmies, crocodiles and chariots competing at the circus.

In my view, Leptis deserves a two-day visit – one to see it all, and a second to go back and dream. The site is an easy commute from Tripoli, which is also worth exploring. With its abundant green flags and ubiquitous portraits of the nation’s leader, Muammar Qadafi, the capital of what is officially known as the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya feels something of a stage set. Many of its grandest buildings date from the colonial era, and the Italians’ ornate banks, piazzas and churches add an operatic mood to the flagship city of this peaceful and welcoming Muslim nation. The atmosphere in the medina is relaxed, the shops hassle-free, and the only jarring note comes from the odd polemical sign that -announces that this pharmacy is “strictly for martyrs’ sons”, or observes how the old British Consulate, built in 1744, was used as a launch pad for scientific expeditions that were missions “to occupy and colonise vital and strategic parts of Africa”.

In my view, Leptis deserves a two-day visit – one to see it all, and a second to go back and dream. The site is an easy commute from Tripoli, which is also worth exploring. With its abundant green flags and ubiquitous portraits of the nation’s leader, Muammar Qadafi, the capital of what is officially known as the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya feels something of a stage set. Many of its grandest buildings date from the colonial era, and the Italians’ ornate banks, piazzas and churches add an operatic mood to the flagship city of this peaceful and welcoming Muslim nation. The atmosphere in the medina is relaxed, the shops hassle-free, and the only jarring note comes from the odd polemical sign that -announces that this pharmacy is “strictly for martyrs’ sons”, or observes how the old British Consulate, built in 1744, was used as a launch pad for scientific expeditions that were missions “to occupy and colonise vital and strategic parts of Africa”.

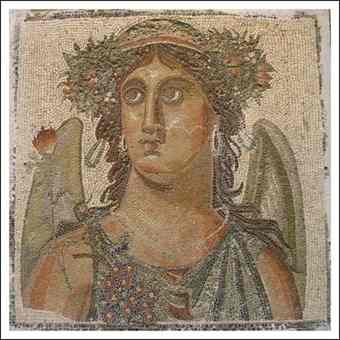

One sight not to miss in Tripoli is the Jamahiriya Museum, where many of the greatest treasures from Leptis are now displayed. Here, magnificent busts and sculptures stand frozen in time like children playing a game of musical statues. Venus, Mercury, Apollo, a fit-looking Mars ... The beauty of the gods lingers in my head, along with more modern exhibits like the turquoise VW Beetle Qadafi drove around in the Sixties as he spread his revolution, and an -entire floor devoted to “The Era of the Masses”, where visitors can admire a lovely floral five-piece suite used for entertaining dignitaries.

One sight not to miss in Tripoli is the Jamahiriya Museum, where many of the greatest treasures from Leptis are now displayed. Here, magnificent busts and sculptures stand frozen in time like children playing a game of musical statues. Venus, Mercury, Apollo, a fit-looking Mars ... The beauty of the gods lingers in my head, along with more modern exhibits like the turquoise VW Beetle Qadafi drove around in the Sixties as he spread his revolution, and an -entire floor devoted to “The Era of the Masses”, where visitors can admire a lovely floral five-piece suite used for entertaining dignitaries.

History has left Libya an Arab country with a taste for espresso and macaroni, but there is no wine, just abundant bottles of “The Water of the Great Man-Made River”, which is the result of a long-distance pipe-dream of Qadafi’s that taps underground reservoirs far away in the Sahara. Lorries covered in sand and flights coming in from Niamey and Ouagadougou are a reminder that we are on the fringes of the Sahara. For centuries this was the final stop on the great trans-African caravan routes – today the country’s cosmopolitan air is sustained by oil wealth. Like Castro’s Cuba, Qadafi’s Libya has the weirdly dated feel of a 20th-century revolution that has somehow made it into the 21st – but how long can it last? Quite a while, I fancy, because the Leader – as he is universally known – is only 68. And as Libya opens up to the world, tourism is playing a key role.

History has left Libya an Arab country with a taste for espresso and macaroni, but there is no wine, just abundant bottles of “The Water of the Great Man-Made River”, which is the result of a long-distance pipe-dream of Qadafi’s that taps underground reservoirs far away in the Sahara. Lorries covered in sand and flights coming in from Niamey and Ouagadougou are a reminder that we are on the fringes of the Sahara. For centuries this was the final stop on the great trans-African caravan routes – today the country’s cosmopolitan air is sustained by oil wealth. Like Castro’s Cuba, Qadafi’s Libya has the weirdly dated feel of a 20th-century revolution that has somehow made it into the 21st – but how long can it last? Quite a while, I fancy, because the Leader – as he is universally known – is only 68. And as Libya opens up to the world, tourism is playing a key role.

Since May, US citizens have been allowed to apply for tourist visas, and international hotel chains such as JW Marriott, Sheraton and InterContinental are now establishing themselves in Tripoli. Meanwhile Libya’s 2,000km coastline, blessed with -sunshine and sandy beaches, is ripe for the development of holiday resorts. The air is alive with the sound of projects, including a bold scheme to create “Green Mountain”, the world’s largest sustainable region, which will run on wind and solar power and include several luxury hotels within easy reach of another of Libya’s prime attractions, the ancient Greek city of Cyrene. Sooner or later, I’m sure, the Roman ruins at Ptolemais will get fenced off and tidied up, ready for a daily influx of coach parties. Its venerable mosaics will still be enchanting – but perhaps not so romantic.

Since May, US citizens have been allowed to apply for tourist visas, and international hotel chains such as JW Marriott, Sheraton and InterContinental are now establishing themselves in Tripoli. Meanwhile Libya’s 2,000km coastline, blessed with -sunshine and sandy beaches, is ripe for the development of holiday resorts. The air is alive with the sound of projects, including a bold scheme to create “Green Mountain”, the world’s largest sustainable region, which will run on wind and solar power and include several luxury hotels within easy reach of another of Libya’s prime attractions, the ancient Greek city of Cyrene. Sooner or later, I’m sure, the Roman ruins at Ptolemais will get fenced off and tidied up, ready for a daily influx of coach parties. Its venerable mosaics will still be enchanting – but perhaps not so romantic.

Author: Kipat Wilson | Source: The National [August 05, 2010]