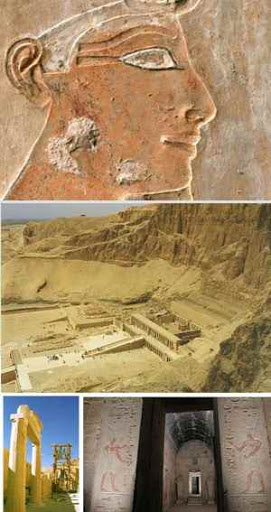

Framed by steep cliffs and poised in elegant relief is the mortuary temple of Deir Al-Bahri, known in ancient times as the "Most Holy of Holies". We now know more than ever before about the plans and ideas of the remarkable woman who built it, says Jill Kamil.

Hatshepsut, as the offspring of the Great Royal Wife Ahmose, was the only lawful heir to the throne of Tuthmosis I. Custom, however, prevented her as a member of the female sex from succeeding as Pharaoh. So she took the only step open to her: she married her half-brother Tuthmosis II.

Hatshepsut, as the offspring of the Great Royal Wife Ahmose, was the only lawful heir to the throne of Tuthmosis I. Custom, however, prevented her as a member of the female sex from succeeding as Pharaoh. So she took the only step open to her: she married her half-brother Tuthmosis II.

"She came to the throne at a crucial time in Egyptian history," said Zbigniew Szafranski, director of the Polish Institute in Cairo at an illustrated talk at the institute last month. "The 18th-Dynasty (1567-1320 BC) emerged from a long-awaited liberation from Hyksos rule; Nubia had become the core of an independent African kingdom; and innovative ideas came from Persia, Palestine, northern Mesopotamia and the Minoan kingdom."

For several years Hatshepsut acted as a typical co- regent, allowing the young Tuthmosis to take precedence in all activities, already there were signs that Hatshepsut was not afraid of flouting tradition. She adopted a new title, "Mistress of the Two Lands", in clear reference to a king's time-honoured title "Lord of the Two Lands"; she commissioned a pair of obelisks to stand in front of the gateway to the Karnak temple complex; and, by the time her obelisks were cut and transported from the quarries at Aswan, she had become a king. She assumed the throne name Makere, "one of many", and she was depicted in relief and statues wearing a royal skirt and ceremonial beard.

The Polish - Egyptian mission has been excavating and restoring the temple of Deir Al-Bahri for 30 years and has recently come upon remarkable evidence on which to hypothesise more about Hatshepsut's life and times. Back in 1969, the team unearthed a small temple built by Tuthmosis III to the south-east of the upper terrace of Hatshepsut's stepped structure, and a year later they found another terrace. Scattered around were hundreds of blocks and fragments of statues from the temple of Hatshepsut, along with plaster casts of blocks from the temple that were taken to the Metropolitan Museum between the years 1911-1931. This enabled enthusiasts to set about reconstructing 26 colossal Osirid statues, many bearing traces of the bright colours with which they were originally painted.

Also discovered -- or should one say excavated from beneath the rubble -- was a temple that Hatshepsut herself appears to have built to the south of the upper terrace. It includes what Szafranski called "a family chapel" dedicated to her parents, their mothers and their grandmothers. "Reading between the lines, this complex subtly reveals a cult of parents," he added.

It was in the seventh year of her reign that Hatshepsut decided to present herself as "King of Upper and Lower Egypt". Indication of this appears in her image, carved in relief, honouring Amun at the entrance to the main sanctuary on the upper terrace, which was first painted pink (the usual skin tone of women), and then over-painted in red, denoting that the god was being honoured by his son. "Her images are beautifully sculpted, even those carved on such high registers on the wall that they could not possibly be seen from the ground. "Evidently she employed the most talented artists in her workshop," Szafranski said.

Indeed, it was her most talented architect, Senmut, who designed the terraced temple for Hatshepsut. "[It] was dramatically different from New Kingdom temples because it was meant to function as a memorial monument, sharing such components as gates, pillars, columns, Osirid statues and sphinxes," Szafranski said. In fact, when approaching the temple from the east one becomes aware that, far from belittling the temple, the stark purity of the cliffs to its rear -- water-worn for thousands of years by hot winds and flash floods forming deep cracks and crevices -- forms a dramatic backcloth.

The structure appears to have been inspired by the adjacent 11th- Dynasty temple built by Hatshepsut's distant predecessor Pharaoh Mentuhotep II (whose temple has also been restored), but it was carried out on a very much larger scale. Senmut adopted the idea of the terrace and added an extra tier, so that the whole temple comprised courts, one above the other, with connecting, inclined planes at the centre. The Polish mission has recently been hard at work on the upper terrace, a festival courtyard and two chambers which were added later -- one in honour of Hathor and devoted to the cult of the queen and her parents, and the other devoted to Anubis. These will soon be open to the public.

"Examining the innovative architecture, especially the large statue of Hatshepsut herself in the form of Osiris in what is known as the Coronation Portico, and also the reliefs on each side of a doorway showing her wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt (to the left), and the Double Crown (to the right), one gets the impression that Hatshepsut herself influenced the project, and may indeed have personally designed her chapel towards the end of her reign," Szafranski said.

The sanctuary of Hatshepsut has a vaulted ceiling and some of the wall paintings bear a marked resemblance to those to be found in Old Kingdom tombs at Saqqara. Here are such scenes as Hatshepsut in front of an offering table, and registers of offering bearers. One cannot help but feel, along with Szafranski, that a little of Hatshepsut's whim and fancy went into the elaboration of this most magnificent of mortuary temples.

Hatshepsut had two tombs. The first she had dug in the Valley of the Kings, where all members of the royal family were laid to rest in the 18th Dynasty. The second was in Taket Zeid Valley, to the south of Deir Al-Bahri overlooking the royal valley. Hatshepsut's mummy was found in neither. It has been suggested that her body may be one of the couple of "unknown woman" found in the shaft at Deir Al-Bahri, but this is by no means certain.

Deir Al-Bahri is best viewed early in the morning when the sun is low in the sky and the air is cool. Later in the day it tends to be very hot and the reliefs are all but invisible. You'll want to see details of the famous colonnades of the voyage to Punt and the Birth Colonnade in their best light. The former commemorates an expedition ordered by Hatshepsut to the East African/Somali coast to bring back myrrh and frankincense trees to be planted on the terraces of her temple, where, at the centre of a long wall, is a scene of the queen (defaced) offering the fruits of her expedition to Amun: frankincense trees, wild game, cattle, electrum and bows. The Birth Colonnade includes a scene of the ram- headed Khnum shaping Hatshepsut and her ka on a potter's wheel. Among the particularly fine representations is one of the queen mother, Ahmose, full with child and radiating joy as she stands dignified in her pregnancy, being led to the birth room.

Source: Al Ahram Weekly [September 25, 2010]