Iowa, Wisconsin and Minnesota states in the Upper Midwest are not usually associated with advanced Native American cultures by the general public in other areas of the United States. Undoubtedly, people residing in the vicinity of this region’s numerous mound sites, are very much aware of their area’s indigenous architectural heritage, but these mounds do not seem to get the national or international exposure of those farther south in the Mississippi River Basin, or in the Southeastern United States. Iowa probably once contained 10,000 mounds. Many of the smaller ones have been plowed under or obliterated by erosion, but enough remain to give evidence of a substantial indigenous occupation.

The Upper Mississippi River Basin in what is now eastern Iowa contained a concentration of indigenous occupants during the Woodland (800 BC - 900 AD) and Mississippian (900 AD – 1300 AD) Cultural Periods. After about 1300 AD, the region appears to have been almost uninhabited for about 300 years.

The Upper Mississippi River Basin in what is now eastern Iowa contained a concentration of indigenous occupants during the Woodland (800 BC - 900 AD) and Mississippian (900 AD – 1300 AD) Cultural Periods. After about 1300 AD, the region appears to have been almost uninhabited for about 300 years.

During the Early Woodland Period (800 AD – 200 AD) the indigenous people of eastern Iowa traded extensively with neighboring regions, but also acquired some artifacts and minerals from other areas of North America. Evidently, the technology for making pottery reached Iowa from the Southeastern United States around 800 BC. A few very large burial mounds were constructed. Their size may reflect continued construction into the Middle and Late Woodland Periods. An interesting feature of many burials during this era was that prior to burial, the human remains were coated in red ochre. Because of this burial tradition, archaeologists label this early mound-building people, the Red Ochre Culture.

Around 200 AD the Native peoples of eastern Iowa began absorbing increasing cultural influence from the Hopewell Culture of southeastern Ohio. The inhabitants did not build the large geometric earthen complexes of the Hopewell Heartland, nor did their ceramics approach the sophistication of the Hopewell’s or Swift Creek Culture in the Southeast. Some burial mounds were constructed, however.

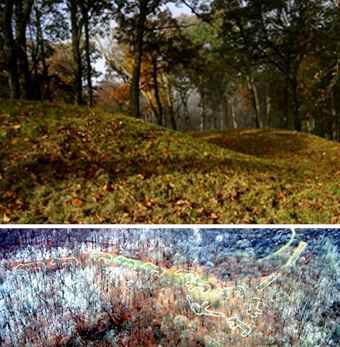

After the Hopewell Culture waned around 500 AD, the indigenous peoples of Iowa, southeastern Minnesota and southwestern Wisconsin began evolving their own unique cultural traits. They still did not build many geometric earthworks, but instead began building many mounds in the shapes of animals, birds, cones and sometimes, humans. Archaeologists call these types of earthworks, effigy mounds. Many of these effigy mounds were enormous, spanning several hundred feet. The earth for these mounds would have been excavated with crude tools of bone and stone, then carried to the site in baskets. The largest mounds would have required thousands of man-hours of labor to complete.

Effigy Mounds National Monument is maintained by the National Park Service and contains three separate units. The National Monument is located in Clayton and Alamakee Counties, Iowa. The North (67 mounds) and South Units (29 mounds) are near the Mississippi River. The Sny Magill Unit contains 112 mounds and is about 11 miles south of the other two units. The NPS facilities for visitors are all located in the North & South Units, which are much easier to reach. Iowa’s major mound sites are concentrated along the eastern edge of the state, and therefore are easily accessed by highways running parallel to the Mississippi River.

The builders of the mounds in Iowa were probably Northern Siouan. At the time, that Europeans first reached the region, the Mississippi River Basin was occupied by the Illini, who were of Algonquian stock and related to the Potawatomie and Obijwe. The Algonquians are believed to have migrated into the Upper Mississippi Basin from the east in late Pre-European times, but this is really not known for sure.

Why were these effigy mounds built?

Being both of Native American descent and not a professional archaeologist, this Examiner can be somewhat more speculative in the interpretation of the hundreds of effigy mounds in Iowa, Wisconsin and Minnesota. The following are possible alternative explanations of these earthworks.

1. Sacred locations associated with clans: Most, but not all, of the effigy mounds portray animals that were symbolic of many Native American clans. It is known that the ancestors of the tribes of the Midwest dispersed during certain seasons of the year, but then came together for communal festivities and trade. Perhaps clan-related rituals involved the creation of earthen manifestations of the clan animal.

2. Portrayal of Native American constellations in the heavens: It is known that many indigenous cultures recognized the clusters of stars and planets in the night time sky. Just as in European, African and Asian cultures, these clusters were given the names of objects on Earth. Perhaps, when dispersed extended families and bands came together for seasonal communal events, the construction of earthen effigies of objects in the night time sky were part of the traditional belief system.

3. “Y’all come back, hear?” signs for extraterrestrial visitors: Several Native American tribes have traditions that humanoids visited them in the past. My own Creek tribe has a tradition that members of the Wind Clan are the descendants of marriages between extremely tall humanoids and the Creek’s Muskogean ancestors. The famous Nazca lines in a Peruvian desert plateau are believed to have been created between 400 AD and 650 AD. This construction period would be contemporary with many of the Upper Mississippi Valley effigy mounds. However, the construction the mounds was entirely different than those in Peru.

It should be emphasized that any interpretation of the Upper Mississippi effigy mounds would be speculative. The only statement that can be made with any degree of certainty is that these mounds were built by Native Americans for religious purposes.

Author: Richard Thornton | Source: Examiner [September 26, 2010]