“What have the Romans ever done for us?” asked an aggrieved man in the Monty Python film “Life of Brian,” only to be met with a roll call of obvious benefits -- sanitation, irrigation, roads -- that could be laid at the occupier's door.

Like the rest of the Mediterranean, Turkey was once a part of the sprawling Roman Empire, and reminders of such Latin refinements can be found at its many archeological sites. Where Turkey is more unusual is that it is also littered with reminders of much less famous civilizations. There are the Phrygians around Gordion, the Lydians around Sardis, the Carians around Bodrum, and the Pamphylians around Antalya. Most conspicuously, there were the Lycians and Greeks who left a legacy of beautiful buildings and monuments strung out along the Turquoise Coast between Dalyan and Phaselis.

Like the rest of the Mediterranean, Turkey was once a part of the sprawling Roman Empire, and reminders of such Latin refinements can be found at its many archeological sites. Where Turkey is more unusual is that it is also littered with reminders of much less famous civilizations. There are the Phrygians around Gordion, the Lydians around Sardis, the Carians around Bodrum, and the Pamphylians around Antalya. Most conspicuously, there were the Lycians and Greeks who left a legacy of beautiful buildings and monuments strung out along the Turquoise Coast between Dalyan and Phaselis.

Not a lot is known about the Lycians, although they appear to have emerged in Anatolia some time between 4000 and 3000 B.C. Fiercely independent, they seem to have lived in a string of city-states linked together by the powerful Lycian Federation, which managed to hold out against the all-conquering Romans until A.D. 43. Even non-experts can easily learn to detect the past presence of the Lycians thanks to their distinctive funerary monuments, which come in three separate forms. In the first place there are the plain and hefty stone sarcophagi of the type to be seen in Fethiye high street, on the outskirts of Patara, and at the top of Uzun Çarşı in Kaş. Then there are pretty rock-cut tombs with carved paneling that resemble older wooden prototypes; tombs like this can be seen in the necropolis at Xanthos and backing the great theater at Myra (Demre). Finally, and most impressively, there are the spectacular rock-cut tombs that look like delicate miniature temples that can be seen at the back of Fethiye and gazing down on the İztuzu River in Dalyan. With that in mind, here are our suggestions for an introductory trawl round the heartlands of Lycia.

Not a lot is known about the Lycians, although they appear to have emerged in Anatolia some time between 4000 and 3000 B.C. Fiercely independent, they seem to have lived in a string of city-states linked together by the powerful Lycian Federation, which managed to hold out against the all-conquering Romans until A.D. 43. Even non-experts can easily learn to detect the past presence of the Lycians thanks to their distinctive funerary monuments, which come in three separate forms. In the first place there are the plain and hefty stone sarcophagi of the type to be seen in Fethiye high street, on the outskirts of Patara, and at the top of Uzun Çarşı in Kaş. Then there are pretty rock-cut tombs with carved paneling that resemble older wooden prototypes; tombs like this can be seen in the necropolis at Xanthos and backing the great theater at Myra (Demre). Finally, and most impressively, there are the spectacular rock-cut tombs that look like delicate miniature temples that can be seen at the back of Fethiye and gazing down on the İztuzu River in Dalyan. With that in mind, here are our suggestions for an introductory trawl round the heartlands of Lycia.

Dalyan: Are they Lycian or are they Carian? The much-photographed tombs at Dalyan are actually attached to the nearby archeological site at Kaunos which is registered at a Carian site. But architecture recognizes no geographical boundaries, and it seems that the Carians preferred to be buried in Lycian style, hence the temple-shaped tombs that keep guard over the tour boats as they ply their way up and down the river.

Dalyan: Are they Lycian or are they Carian? The much-photographed tombs at Dalyan are actually attached to the nearby archeological site at Kaunos which is registered at a Carian site. But architecture recognizes no geographical boundaries, and it seems that the Carians preferred to be buried in Lycian style, hence the temple-shaped tombs that keep guard over the tour boats as they ply their way up and down the river.

Fethiye: Fethiye was once the Lycian settlement of Telmessos, and carved into the rock face at the back of the town is the striking, temple-shaped Tomb of Amyntas. Nothing is known about this presumably wealthy and important individual bar the fact that he was the son of one Hermagios, as recorded in Greek on the facade. Rather more telling is a trilingual stele that can be seen in Fethiye Museum although it was excavated at the Letoon, near Xanthos. Dating back to 358 B.C., it turned out to be the Rosetta Stone of Lycia, inscribed in Lycian, Greek and Aramaic, thereby helping forensic linguists crack the Lycian hieroglyphics.

Fethiye: Fethiye was once the Lycian settlement of Telmessos, and carved into the rock face at the back of the town is the striking, temple-shaped Tomb of Amyntas. Nothing is known about this presumably wealthy and important individual bar the fact that he was the son of one Hermagios, as recorded in Greek on the facade. Rather more telling is a trilingual stele that can be seen in Fethiye Museum although it was excavated at the Letoon, near Xanthos. Dating back to 358 B.C., it turned out to be the Rosetta Stone of Lycia, inscribed in Lycian, Greek and Aramaic, thereby helping forensic linguists crack the Lycian hieroglyphics.

Tlos: Inland from Fethiye is the impressive site of Tlos, one of the oldest of the Lycian cities although very little is known about its history. The ruins center on a cluster of rock-cut tombs ringing a dramatic promontory of rock with magnificent views. The most interesting of the tombs is somewhat out on a limb but bears a carving of the Greek hero Bellerophon riding the winged horse Pegasus, hence its name, the Tomb of Bellerophon.

Tlos: Inland from Fethiye is the impressive site of Tlos, one of the oldest of the Lycian cities although very little is known about its history. The ruins center on a cluster of rock-cut tombs ringing a dramatic promontory of rock with magnificent views. The most interesting of the tombs is somewhat out on a limb but bears a carving of the Greek hero Bellerophon riding the winged horse Pegasus, hence its name, the Tomb of Bellerophon.

Pinara: These days Tlos is well-established on the day-trip circuit. Pinara takes a little more effort to get to, although its wonderfully unspoilt woodland setting makes all the sweating well worth while. Once again the fine carved tombs and their dramatic setting make up for a dearth of hard facts about the site, once one of the largest of the Lycian towns.

Pinara: These days Tlos is well-established on the day-trip circuit. Pinara takes a little more effort to get to, although its wonderfully unspoilt woodland setting makes all the sweating well worth while. Once again the fine carved tombs and their dramatic setting make up for a dearth of hard facts about the site, once one of the largest of the Lycian towns.

Xanthos: Just inland from the coast, the city of Xanthos was more than usually determined to remain independent, so much so in fact that in 540 B.C. when it was staring defeat in the face at the hands of the Persian general, Harpagus, the women and children immolated themselves on funeral pyres while their men went down fighting. In 42 B.C. as the Roman general, Brutus, descended on them the locals once again preferred to kill themselves rather than submit. The site was once adorned with striking sculptures that were removed in 1842 when the traveler Charles Fellowes had most of them shipped to the British Museum; today visitors have to make do with copies. A huge Lycian necropolis lurks unnoticed to the rear of the site.

Xanthos: Just inland from the coast, the city of Xanthos was more than usually determined to remain independent, so much so in fact that in 540 B.C. when it was staring defeat in the face at the hands of the Persian general, Harpagus, the women and children immolated themselves on funeral pyres while their men went down fighting. In 42 B.C. as the Roman general, Brutus, descended on them the locals once again preferred to kill themselves rather than submit. The site was once adorned with striking sculptures that were removed in 1842 when the traveler Charles Fellowes had most of them shipped to the British Museum; today visitors have to make do with copies. A huge Lycian necropolis lurks unnoticed to the rear of the site.

The Letoon: Nearer to the sea, the now swampy Letoon was once a vast temple that seems to have been the main religious sanctuary of the Lycian Federation as well as the site of an oracle. It was dedicated to the Greek goddess Leto, the mother of the twins Apollo and Artemis, who had stopped here to drink from a spring after it was shown to her by wolves. It was after those same wolves (lykos in Greek) that the surrounding area was supposedly renamed Lycia.

The Letoon: Nearer to the sea, the now swampy Letoon was once a vast temple that seems to have been the main religious sanctuary of the Lycian Federation as well as the site of an oracle. It was dedicated to the Greek goddess Leto, the mother of the twins Apollo and Artemis, who had stopped here to drink from a spring after it was shown to her by wolves. It was after those same wolves (lykos in Greek) that the surrounding area was supposedly renamed Lycia.

Patara: Patara is best known for its long and lovely beach, and for an ancient theater that has emerged virtually unscathed from the sand. The signs of its Lycian origins are abundant, however, since huge sarcophagi lie cracked open by the road as you start the walk down from Gelemiş village. Brutus had more success here than he did with Xanthos by taking the women hostage, threatening to kill them, and then releasing them to show his decency.

Patara: Patara is best known for its long and lovely beach, and for an ancient theater that has emerged virtually unscathed from the sand. The signs of its Lycian origins are abundant, however, since huge sarcophagi lie cracked open by the road as you start the walk down from Gelemiş village. Brutus had more success here than he did with Xanthos by taking the women hostage, threatening to kill them, and then releasing them to show his decency.

Kaş, Kale and Simena: The lovely little seaside resort of Kaş was once a Lycian stronghold called Antiphellos, although there's not a great deal to show for that today bar the striking Lion Tomb at the top of picturesque Uzun Çarşı, which takes its name from the lions carved on its two-storey facade. The words inscribed on it remain mysterious, a reminder that the stele from Letoon was not enough to entirely pin down ancient Lycian. From Kaş you can take a delightful boat ride to Kale, the village on a promontory jutting out into the sea which is topped with the ruins of a Crusader-era castle but which also boasts a Lycian necropolis of giant stone sarcophagi tripping down the hillside.

Kaş, Kale and Simena: The lovely little seaside resort of Kaş was once a Lycian stronghold called Antiphellos, although there's not a great deal to show for that today bar the striking Lion Tomb at the top of picturesque Uzun Çarşı, which takes its name from the lions carved on its two-storey facade. The words inscribed on it remain mysterious, a reminder that the stele from Letoon was not enough to entirely pin down ancient Lycian. From Kaş you can take a delightful boat ride to Kale, the village on a promontory jutting out into the sea which is topped with the ruins of a Crusader-era castle but which also boasts a Lycian necropolis of giant stone sarcophagi tripping down the hillside.

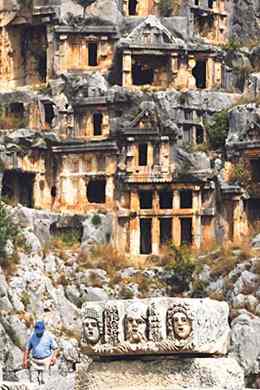

Myra: These days the buzz at Demre/Kale tends to be about the Church of St. Nicholas, with its supposed links with the original Father Christmas. Just inland, though, stands an impressive Roman theater with, behind it, a wall of wonderful Lycian tombs carved in what are thought to be the shape of ancient houses. The best are decorated with carvings depicting a mix of military and domestic scenes.

Myra: These days the buzz at Demre/Kale tends to be about the Church of St. Nicholas, with its supposed links with the original Father Christmas. Just inland, though, stands an impressive Roman theater with, behind it, a wall of wonderful Lycian tombs carved in what are thought to be the shape of ancient houses. The best are decorated with carvings depicting a mix of military and domestic scenes.

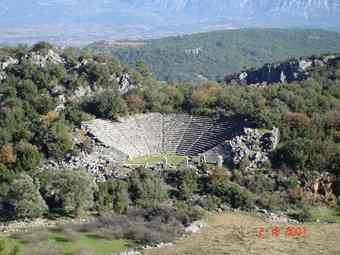

Arykanda and Limyra: Probably because a visit involves a detour inland along the Finike to Elmalı road, beautiful Arykanda receives far fewer visitors than most of the Lycian sites, despite its dramatic location and a marvelously preserved theater and stadium with spectacular views. Arykanda is so striking that the ruins at Limyra, much closer to Finike, can seem relatively insignificant. The site has a beautiful, bucolic feel to it though, especially at this time of year as the trees take on their autumnal hues.

Arykanda and Limyra: Probably because a visit involves a detour inland along the Finike to Elmalı road, beautiful Arykanda receives far fewer visitors than most of the Lycian sites, despite its dramatic location and a marvelously preserved theater and stadium with spectacular views. Arykanda is so striking that the ruins at Limyra, much closer to Finike, can seem relatively insignificant. The site has a beautiful, bucolic feel to it though, especially at this time of year as the trees take on their autumnal hues.

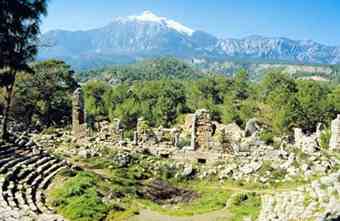

Phaselis: With its triple harbor, Phaselis was always ideally place to scoop the local import/export trade, although, on the border with Pamphlia, it only seems to have become part of the Lycian Federation in the second century B.C. Its proximity to Antalya ensures that it's a prime target for tour groups. Its wonderful wooded location makes it, however, a great place to wind up a whirlwind tour of ancient Lycia.

Phaselis: With its triple harbor, Phaselis was always ideally place to scoop the local import/export trade, although, on the border with Pamphlia, it only seems to have become part of the Lycian Federation in the second century B.C. Its proximity to Antalya ensures that it's a prime target for tour groups. Its wonderful wooded location makes it, however, a great place to wind up a whirlwind tour of ancient Lycia.

Source: Todays Zaman [October 11, 2010]