More than 150 years ago, a Crow warrior — a man honored by his Apsaalooke people and feared by his enemies — had his war exploits painted on a buffalo hide tanned by his proud wife.

No one knows his name today, but his Crow contemporaries would have been able to identify him by the stories drawn on his robe.

No one knows his name today, but his Crow contemporaries would have been able to identify him by the stories drawn on his robe.

Enemies, primarily Blackfoot warriors vying for resources and power in the prime hunting grounds of Montana, would have recognized him as a formidable opponent by the number of vanquished foes depicted.

“It was his biography. It tells his story. It tells the story of the Crow Tribe,” said Patrick Hill, Crow historian and artist.

Hill and Little Bighorn College archaeology professor Tim McCleary spent several days in Washington, D.C., along with tribal historian Joe Medicine Crow and Calgary anthropologist Arni Brownstone, interpreting the robe for the Smithsonian Institution.

When the National Museum of the American Indian, a branch of the Smithsonian, opens its major new exhibit, Infinity of Nations, in New York City on Oct. 20, the robe will be one of its centerpieces.

Curator Cecile Ganteaume designed the exhibit around 10 objects that serve as “regional focal points.” The rare and beautiful warrior robe was chosen as the focal art piece for the Plains and Plateau section.

Infinity of Nations is described as a survey of the museum’s vast collection of native art from the Western Hemisphere. More than 700 pieces — some of them thousands of years old — will be included in the exhibit. It represents cultures from Alaska to Chile.

Infinity of Nations is described as a survey of the museum’s vast collection of native art from the Western Hemisphere. More than 700 pieces — some of them thousands of years old — will be included in the exhibit. It represents cultures from Alaska to Chile.

The exhibit halls will open to benefactors and museum members on Oct. 20 with a gala celebration. The general public will get its first look on Oct. 23.

Although they won’t be there in person, Hill and McCleary will be featured in audio, video and touch-screen programs explaining Crow warfare and history and talking about Crow Country.

“The idea of the exhibit is to have an object that can be placed in time and place and tied to a specific culture,” McCleary said in an interview in Billings last week.

The Crow buffalo robe fits the exhibit perfectly. It can be placed squarely in the middle of the 19th century, both by the artwork itself and by its documented history.

Records show that New York artist William de la Montagne Cary acquired the robe at Fort Benton in 1861, McCleary said.

Cary bought the robe from a man a witness to the transaction described as either a Blackfoot or a Cree, but most likely a Blackfoot, McCleary said. Hill and McCleary could see at a glance that it was unmistakably Crow.

How it came into the hands of an enemy Blackfoot warrior provided for a lot of interesting speculation, the two men said.

How it came into the hands of an enemy Blackfoot warrior provided for a lot of interesting speculation, the two men said.

“He could have taken it from a Crow warrior he killed in battle,” McCleary said. “The Blackfoot liked to bring back clothing to prove they had killed an enemy so they could claim war honors.”

Hill said that the Blackfoot warrior may not have obtained the robe through bloodshed. The Crow owner was of high status, he said.

“It could have been a chiefly gift during a time of peace,” he said.

While there are still many examples of Crow narrative artwork in pictographs in Montana and Wyoming, robes from that era depicting the life of a specific individual are rare. McCleary said he has heard of just three others.

The Little Bighorn College professor earned his doctorate in archaeology in 2008 after completing a dissertation on rock art. When the Smithsonian was looking for experts to interpret the robe, it contacted Stu Conner of Billings, one of the foremost rock-art experts in the country. He referred them to McCleary.

After obtaining the consent of the Crow Cultural Committee to work on the project, McCleary said that he thought the team should include a Crow tribal member and artist. That’s where Hill, owner of the Center of the Circle Studio in Crow Agency, came in.

After obtaining the consent of the Crow Cultural Committee to work on the project, McCleary said that he thought the team should include a Crow tribal member and artist. That’s where Hill, owner of the Center of the Circle Studio in Crow Agency, came in.

Their expertise was supplemented by respected elder and historian Joe Medicine Crow and Brownstone, the anthropologist. McCleary said Brownstone’s expertise in American Indian art has taken him to Europe many times to examine items collected there by 19th-century visitors touring the West.

In advance of being placed on permanent exhibit at the New York museum, the fragile buffalo skin was conserved at the Smithsonian in Washington. That’s where McCleary and Hill first saw it in December of 2006.

The robe was laid out on the floor on acid-free tissue, Hill said. Conservators perched on ladders above it, conducted the restoration without touching the delicate hide more than necessary.

It took a year to complete the job, Hill said.

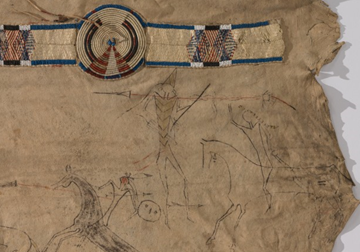

Sewn down the length of the hide is a finely stitched pattern of beadwork and porcupine quills wrapped in horse hair. The horse-hair quills — unique to Crow artisans of the period — were woven in a design of lines and circles.

A triangle of red “trade” cloth identified with the mid-1800s helped confirm the date. Triangles were symbols for horses.

A triangle of red “trade” cloth identified with the mid-1800s helped confirm the date. Triangles were symbols for horses.

But more interesting to the artists and historians examining it were the drawings that covered the robe.

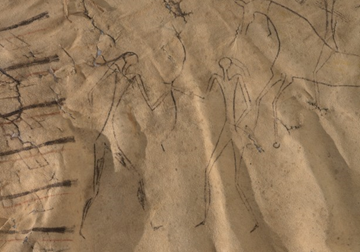

Some are easily recognizable. Near the head of the hide, 11 clearly identifiable trade muskets, probably from the earlier fur-trade era, are painted in a long row.

“They represent 11 guns he had taken from enemies,” McCleary said.

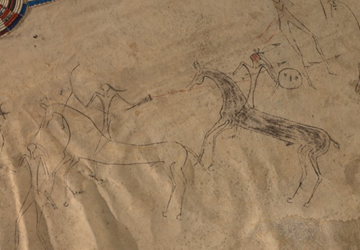

Drawings covering the robe would have been read top to bottom and right to left, he said. They would have been designed to be read as the warrior wore the robe over his shoulders at parades and at ceremonies where warriors proclaimed their war deeds.

“In Crow society, a warrior had to achieve four specific honors before he could become a chief,” Hill said.

The warrior had to strike a live enemy in battle, capture a picketed enemy horse, take an enemy’s weapon in battle and lead a successful war party. In the six vignettes on the robe, the warrior shows that he has achieved all those goals except the last, leading a successful war party.

“This guy was well on his way to becoming a chief,” McCleary said.

“This guy was well on his way to becoming a chief,” McCleary said.

In the battle scenes, the victorious warrior is always depicted on the right and the vanquished enemy on the left, McCleary said. A Crow warrior could be identified by long, flowing hair on the back of his head and a crest of upright hair on top symbolizing the way the tribe’s warriors wore their hair in battle.

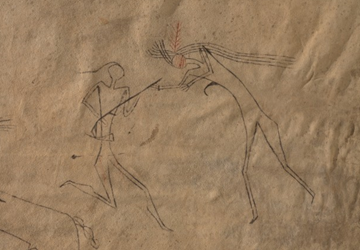

The first scene shows the warrior, his face painted red, running to seize a gun from a wounded enemy. A musket ball makes a path through the enemy’s torso and leaves a trail of blood at its exit.

In the second scene, the warrior is shown preparing to count coups on an enemy by touching him with his lance. Previous war honors are illustrated by two stripes on his horse.

The third scene portrays a pitched battle where the Crow warrior is wounded in the thigh. An enemy is shooting at him, but his bullet misses. The enemy is then killed by a shot from the Crow warrior.

The fourth vignette shows the warrior counting coups on an escaping enemy who has fired two arrows at the Crow hero.

In the fifth scene, the warrior grabs a bow from an enemy. The final drawing represents the 11 muskets.

Each tribal group used its own symbols or ideograms, McCleary said. For instance, an “X” to the Crows symbolized a live enemy touched in battle. Other cultures on the Northern Plains may not have used the same symbol, but they knew what it meant when they saw it, he said.

Each tribal group used its own symbols or ideograms, McCleary said. For instance, an “X” to the Crows symbolized a live enemy touched in battle. Other cultures on the Northern Plains may not have used the same symbol, but they knew what it meant when they saw it, he said.

There were universal symbols, too, McCleary said. A circle was understood to mean that an enemy had made a strong stand.

Symbols were beginning to represent larger ideas, he said.

“Had Europeans not come, these symbols would probably have developed into a recognizable writing system,” he said.

Author: Lorna Thackeray | Source: Billings Gazette [October 12, 2010]