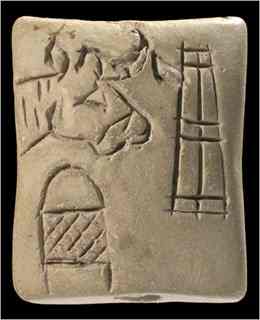

One of the stars of the Oriental Institute’s new show, “Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond,” is a clay tablet that dates from around 3200 B.C. On it, written in cuneiform, the script language of ancient Sumer in Mesopotamia, is a list of professions, described in small, repetitive impressed characters that look more like wedge-shape footprints than what we recognize as writing.

In fact “it is among the earliest examples of writings that we know of so far,” according to the institute’s director, Gil J. Stein, and it provides insights into the life of one of the world’s oldest cultures.

In fact “it is among the earliest examples of writings that we know of so far,” according to the institute’s director, Gil J. Stein, and it provides insights into the life of one of the world’s oldest cultures.

The new exhibition by the institute, part of the University of Chicago, is the first in the United States in 26 years to focus on comparative writing. It relies on advances in archaeologists’ knowledge to shed new light on the invention of scripted language and its subsequent evolution.

The show demonstrates that, contrary to the long-held belief that writing spread from east to west, Sumerian cuneiform and its derivatives and Egyptian hieroglyphics evolved separately from each another. And those writing systems were but two of the ancient forms of writing that evolved independently. Over a span of two millenniums, two other powerful civilizations — the Chinese and Mayans — also identified and met a need for written communication. Writing came to China as early as around 1200 B.C. and to the Maya in Mesoamerica long before A.D. 500.

“It was the first true information revolution,” Mr. Stein said. “By putting spoken language into material form, people could for the first time store and transmit it across time and space.”

The Oriental Institute spent two years assembling the show, much of which comes from its own collections. However, it did borrow important Sumerian pieces from other institutions, including the clay tablet from the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin, which has never before been seen in the United States.

The Oriental Institute, which opened in 1919, was heavily financed by John D. Rockefeller Jr., who had been greatly influenced by James Henry Breasted, a passionate archaeologist. Abby Rockefeller had read his best seller “Ancient Times” to her children.

Today the institute, which still has seven digs going on, boasts objects from excavations in Egypt, Israel, Syria, Turkey and Iraq. Many artifacts were acquired from joint digs with host countries with which the findings were shared. Among the institute’s prized holdings is a 40-ton winged bull from Khorsabad, the capital of Assyria, from around 715 B.C.

The exhibition, which runs through March 6, focuses heavily on the Sumerian civilization that flourished between 3500 B.C. and 1800 B.C. in what is now southern Iraq. Until the 1950s experts had believed that the Sumerians influenced the Egyptians, spreading the use of writing westward. But in the 1950s Günther Dryer, a German archaeologist, found writing on bone and ivory tags in an elaborate, probably royal burial site at Abydos in southern Egypt. The depth at which they were buried and subsequent carbon tests proved the pieces to be as old as Sumerian works. Because the marks were different in style, scholars believe that the Egyptians developed their own writing system independently.

The exhibition, which runs through March 6, focuses heavily on the Sumerian civilization that flourished between 3500 B.C. and 1800 B.C. in what is now southern Iraq. Until the 1950s experts had believed that the Sumerians influenced the Egyptians, spreading the use of writing westward. But in the 1950s Günther Dryer, a German archaeologist, found writing on bone and ivory tags in an elaborate, probably royal burial site at Abydos in southern Egypt. The depth at which they were buried and subsequent carbon tests proved the pieces to be as old as Sumerian works. Because the marks were different in style, scholars believe that the Egyptians developed their own writing system independently.

Experts are still struggling to understand just how writing evolved, but one theory, laid out at the Oriental Institute’s exhibition, places the final prewriting stage at 3400 B.C., when the Sumerians first began using small clay envelopes like the ones in the show. Some of the envelopes had tiny clay balls sealed within. Archaeologists theorize that they were sent along with goods being delivered; recipients would open them and ensure that the number of receivables matched the number of clay tokens. The tokens, examples of which are also are in the show , transmitted information, a key function of writing.

Writing as a carrier of narrative did not evolve for another 700 years, as shown in the inscribed versions of the Sumerian epic tale of Gilgamesh, also on display in the institute’s general collection.

Although Egyptian hieroglyphics are more broadly familiar than cuneiform, Sumerian writing was done on clay, which is more durable than papyrus. As a result, Sumer is among the best documented of ancient societies.

An important part of the Oriental Institute exhibition’s allure is that it describes some of the unknowns that still intrigue archaeologists, including the birth of the alphabet. The show includes a plaque dated from 1800 B.C. that contains signs that seem to be inspired by Egyptian hieroglyphics but that are actually the earliest letters of an alphabetic script representing Semitic languages. It was found near an ancient turquoise mining site in the Sinai Peninsula, in what was part of ancient Egypt, but the men who worked there spoke the Semitic language of the Canaanites.

Because this is one of the first examples of the use of the alphabetic letters, it suggests that the alphabet was inspired by hieroglyphics. Still, no one really knows who the miners were, if they were literate or how they adapted hieroglyphics to write a western Semitic language. But in later discoveries those same forms make up parts of words.

An alphabetic language has a limited number of signs and is easier to both use and to teach than a representational system like hieroglyphics. An alphabet allows a more rapid spread of literacy and communications. Today almost all languages except Chinese and Japanese are alphabetic. The lack of an alphabet makes Chinese particularly difficult for foreigners. But if Chinese bears little similarity to languages elsewhere in the world, its origins — like the origins of hieroglyphics — have to do with the gods. Bones from ancient Chinese tombs, also on display at the Oriental, were used to help divine the future. The inscriptions on them are the earliest form of Chinese writing, and they make statements about events, such as a battle or the birth of a royal child, and also, in effect, ask how they will come out. Hot brands were put into hollows carved into turtle shells, and the configurations of the resulting cracks were interpreted as answers to important questions.

Less is known about the earliest phases and origin of Mayan writing. Much of the work under way concentrates on artifacts from the Mayans’ later period, around A.D. 600. The exhibition includes a Mayan stone monument showing the face of a dead Mayan lord. It carries his name and the date of the dedication of the stone.

To Christopher E. Woods, associate professor of Sumerology at the University of Chicago and the curator of the show, it was important to include examples from all four cultures because the goal of the exhibition was “to present and describe the four times in history when writing was invented from scratch.”

Author: Geraldine Fabrikant | Source: The New York Times [October 19, 2010]