The French village attracts 'all different types' drawn by the mystery of an inexplicably rich priest in the 19th century. For some observers, though, the obsession is just 'pitiable.'

On a wooden table outside his one-room hut, Remy Martinez spreads out a worn-at-the-edges topographical map. On it, he has drawn a circle. Within the circle is a Star of David, and in the center of the star is a dot.

On a wooden table outside his one-room hut, Remy Martinez spreads out a worn-at-the-edges topographical map. On it, he has drawn a circle. Within the circle is a Star of David, and in the center of the star is a dot.

"This is it," the 51-year-old says, pointing. Then he folds up the map quickly, stuffing it into a clear plastic folder he cradles under his arm. He smiles. "That is all I can show you of that."

For two years now, Martinez, a post office worker on most days and a treasure hunter the rest of the time, has lived in the hut and a small trailer atop an isolated, grassy hill spotted with blue wildflowers. He says he is meant to live out his days here.

"I wouldn't leave this place, not even for a woman," he says more than once.

Martinez is in the secret business of hunting for treasure, and he believes he has found an ancient and sacred one.

He is not the only one who has come searching for the hidden riches of Rennes-le-Chateau, a village about a 90-mile drive from the Spanish border that has become the setting for a kind of Gallic "Treasure of the Sierra Madre."

Spouting theories involving everything from the Holy Grail to extraterrestrials, the treasure hunters have been known to abandon jobs and family to come here because of their passion — or, as others would say, their delusion.

Even though no treasure has ever been found, not even a candlestick, the earth around the village has witnessed cave-ins from tunneling hunters. For years, small hillside explosions were common as the seekers resorted to dynamite.

Now, when you walk into the village, a sign warns: "Digging is forbidden."

"I think we are the only village in all of France with a sign like that at its entrance," said Mayor Alexandre Painco. "There are not many places like it. We attract all different types of people."

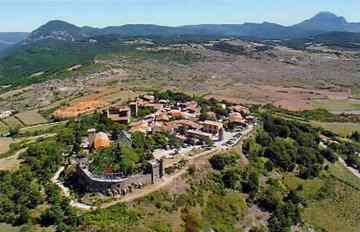

The village of fewer than 100 people, most of them farmers, was forced to build a large parking lot just outside the town walls to accommodate the 150,000 visitors who come every year to learn about its famous mystery and wander winding streets with old stone homes dating to the 8th century.

The mystery goes back more than 100 years. At the end of the 19th century, Rennes-le-Chateau's parish priest, Francois Berenger Sauniere, shocked his neighbors by suddenly spending a fortune renovating the town church and building elaborate gardens, a villa and a neo-Gothic tower, still standing today. His meager salary could not have accounted for the spending, but his strange behavior — digging at night in the village graveyard, and talk of hidden parchments he discovered — seemed to hint at an explanation. As common belief has it, he had discovered treasure.

The mystery goes back more than 100 years. At the end of the 19th century, Rennes-le-Chateau's parish priest, Francois Berenger Sauniere, shocked his neighbors by suddenly spending a fortune renovating the town church and building elaborate gardens, a villa and a neo-Gothic tower, still standing today. His meager salary could not have accounted for the spending, but his strange behavior — digging at night in the village graveyard, and talk of hidden parchments he discovered — seemed to hint at an explanation. As common belief has it, he had discovered treasure.

It wasn't until the 1950s that word spread more widely of the old priest's unaccounted wealth, the source of which he had refused to divulge when asked by church superiors in Paris who suspected he was soliciting money to say extra Masses, in violation of canon law. One villager's account led to another, and a legend was born.

But faux-historical novels about the Sauniere mystery did most of the heavy lifting in the building of the legend. They wove in explanations linked to the area's rich history, which includes 2,500-year-old Celtic and Gallic tribes; heretical medieval Cathar priests and warriors, believed to have hidden treasure of their own; conquering and gold-pillaging Romans; their tough-skinned Visigoth successors, who kept a capital city in nearby Toulouse; and early French monarchs.

Children here grow up learning how these kingdoms, and perhaps their own ancestors, carried back booty from Jerusalem and Rome.

The Dan Brown bestseller "The Da Vinci Code" draws inspiration from the mystery: Its opening chapter is about a Frenchman named Sauniere, who is killed for secrets about the location of the Holy Grail.

Philippe Marlin, local editor and bookstore owner, says it is no wonder there are so many legends about Rennes-le-Chateau.

Sitting at a cafe in the village, he breezes through 4,000 years of local history, naming emperors, vanished tribes and wars as if it was all common knowledge, or that day's news.

"People have been fascinated with the history of the area for years," he says. "It is a land of colossal legends. Here is the land of treasures. There are treasures everywhere," he says. "Add to that the Sauniere mystery, and boom."

Marlin doesn't believe the wilder theories about the sources of Rennes-le-Chateau's still-undiscovered treasure. He does, however, believe treasure must have been left in these parts.

"It is extremely interesting to see how a lot of people need to fabricate falsehoods and to invent stories in order to exist," he says. Some even believe Christ is buried in the hills visible from the town, he says with a laugh, pointing to a small mountain that mystical treasure hunters call "Zion."

When taken to extremes, the search "can turn into forms of paranoia that are sometimes pitiable," he said, remembering a man who worked at a science lab a few hours away, left his wife and children and spent his last cent on a treasure search here.

The last Marlin heard, the man was living in a shack not far away. "Most hunters will keep going and believing in it until their last breath," he says.

"Rennes-le-Chateau is a sticky myth, like flypaper. It attracts everything," Marlin said.

Some treasure hunters around the village appear aware of the risks of their passion, and they warn against, or scoff at, others they believe have gone over the edge. Yet the own theories about the treasure are often remarkably similar. Many seem able to recognize folly in others but assume they themselves must be on the right track.

Some treasure hunters around the village appear aware of the risks of their passion, and they warn against, or scoff at, others they believe have gone over the edge. Yet the own theories about the treasure are often remarkably similar. Many seem able to recognize folly in others but assume they themselves must be on the right track.

"It can also become a heavy burden," Martinez says as he walks down one of his favorite forest paths, with spectacular views of surrounding valleys toward a rock he believes resembles a skull, to him an obvious clue. He notices minute details along the way: a wild red berry oddly placed near the path, a fragment of a fossil about the size of a pebble.

"I know, maybe you think all this is crazy…. And it can take over, becoming all that you can think about.... It can be never-ending," he says. "My family may have had to pay for that."

He stopped talking to his parents about it — they had had enough. And he is careful about what he tells his two teenage boys,whom he visits regularly after separating from his wife of more than 20 years. (The split was not caused by his treasure quest, he says.)

Martinez, who grew up in the countryside near Rennes-le-Chateau, says he has always loved searching for fossils and treasures in these hills. "You have to dream, you have to stay a child."

For more than 30 years now, he has been looking for jewels and gold that he believes were carried back to the area by the Visigoths after they sacked Rome in AD 410. He thinks the treasure lies in the labyrinth of an underground vault, along with parts of an ancient Jewish temple and the body of Jesus, which he thinks was stored there by Knights Templars.

Although finding the treasure was once more important to him, he says that as he has gotten older, the search has become more of a spiritual journey, teaching him about himself and the area's history. His home is full of books about the life of early settlers here, which Martinez enjoys studying down to their clothing habits — allowing him, he says, to better imagine "putting myself in their shoes. They weren't that different from us."

Martinez carefully guards his research, but he does share a few clues (nothing that would give too much away) that have helped him locate the dot on his map.

He says he gathered evidence by decoding incomprehensible Latin phrases found on tombstones in the area or inside the town's 8th century church ("if it doesn't mean anything, it is a code"), drawing geometric figures onto reproductions of ancient texts (or what are believed to be reproductions of ancient texts), studying 17th century paintings and frescoes for symbols, mining the historical record and adding a dash of intuition.

He says he gathered evidence by decoding incomprehensible Latin phrases found on tombstones in the area or inside the town's 8th century church ("if it doesn't mean anything, it is a code"), drawing geometric figures onto reproductions of ancient texts (or what are believed to be reproductions of ancient texts), studying 17th century paintings and frescoes for symbols, mining the historical record and adding a dash of intuition.

His search has led him through the forests around Rennes-le-Chateau to where he is fairly convinced the treasure lies, under a very large rock.

He has not tried to move the rock yet, a practically difficult endeavor, because it is on private property. He is also in a "dilemma" about going into the vault where he thinks the treasure waits for him. His hair might turn white, or he might die. And what if he survived?

"I'm human," he says. "I'd go to Belgium to sell the jewels."

But he says he would take only some of the treasure to pay for his trouble, and leave the rest of the place intact. He sees himself as the treasure's guardian, its protector.

If other people found out, he says, "then what would I do with myself?"

Author: Devorah Lauter | Los Angeles Times [October 05, 2010]