If one tires of urban archaeological sites and is trying to capture some glimpse of ancient Greece amid the commotion and near-endless din of modern Athens, there are plenty of fascinating spots, both large and small, just waiting to be rediscovered and explored outside the city in the magnificent hills and valleys of rural Attica.

These time-worn architectural remains include watchtowers, signalling posts, temporary fieldworks and walled camps. Most impressive, however, are the massively-built towers and fortresses of late Classical and early Hellenistic date (4th and 3rd centuries BC) to be found overlooking the sea at Rhamnous, northeast of Athens, or further inland on commanding heights with stunning views, such as at the northwestern citadels of Phyle and Eleutherae.

Stretching in a protective zone across Attica’s northern frontier, Rhamnous’ fortifications in the east to Egosthena in the west, at Porto Germeno on the Corinthian Gulf, a string of solid military installations are still preserved.

These historically rich places stand as long-silent witnesses to past democratic struggles and the regional turmoil that ultimately overwhelmed Athens after the Battle of Chaeronea in 338BC, during the rise of Macedonia’s power. Presented below is a select gazetteer of sites, drawing partly on American archaeologist James McCredie’s authoritative 1966 study, Fortified Military Camps in Attica, which aims to provide visitors and weekend trampers with a taste of the refreshing, often surprisingly under-populated archaeological and natural wonders of Attica’s ages-old landscape.

Rhamnous (northeastern) and Sounion (southern), coast of Attica

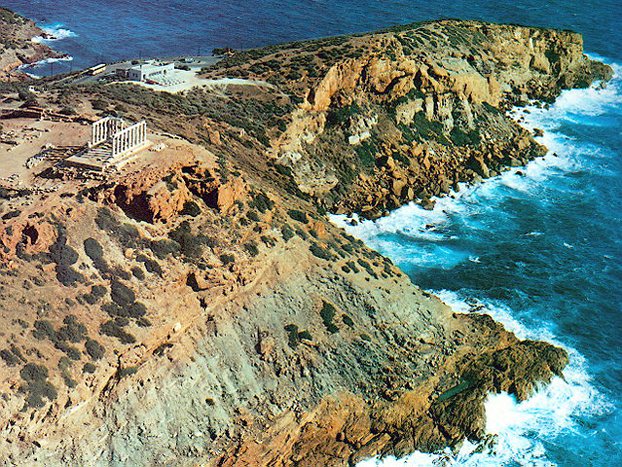

At the large end of the scale of Attica’s ancient military installations are the garrison-forts. In central and eastern Attica, these Classical fortresses, built of finely-cut ashlar blocks, include Eleusis, Phyle, Sounion and Rhamnous. Particularly characteristic are their sophisticated defensive architecture and their locations on borders, major routes, crossroads and key coastal points.

Rhamnous and Sounion became especially important in the late 5th century BC, when the Spartans followed the advice of the traitorous Athenian Alcibiades and seized the strategic hill of Dekeleia, north of Athens, in 412BC. Having thus cut off the city’s major food supply, the Spartans forced the Athenians to seek alternative routes for their vital shipments of Evia grain and other foodstuffs. Rhamnous’ twin harbours replaced the more northerly port of Oropos and served as a naval base from which Athenian warships could safeguard the newly crucial shipping lanes that extended around Cape Sounion to Piraeus.

Although remote, Rhamnous was an Athenian satellite community with clear ties to the mother city’s political, religious and artistic life. Already in the early 5th century BC, Rhamnous had become known for its cult of Nemesis, the goddess of retribution, who was believed to have punished the hubristic Persian attack at Marathon in 480BC by granting victory to the Greeks.

Visible at Rhamnous today are the foundations of a mid-century marble temple of Nemesis, attributed by specialists to the unknown architect who also built the temple of Poseidon at Sounion and the temples of Hephaestus and Ares in the Athenian agora. Lining the main street to Rhamnous are grave monuments that commemorate the town’s prominent families and recall similar 4th century BC monuments in the Kerameikos of Athens. The fortress itself consists of a multi-towered wall that encloses the town and a high, equally fortified acropolis.

Signalling posts were established around Attica at Sounion, and smaller, more lightly fortified sites, including Atene and Vari-Anagyrous on the west coast. The guards at these stations could quickly pass on to Piraeus warnings of approaching enemy forces.

Two walled military camps, on Patroclus Island about 3km west of Sounion and at peninsular Koroni beside Porto Rafti, on the eastern Attica seaboard, were established during the Chremonidean War around 267-261BC. Ptolemy II had sent a fleet of Egyptian triremes, commanded by his general Patroclus, to assist Athens and Sparta against the Macedonians, led by Antigonos Gonatas. Based on the evidence of ancient texts (Pausanias and Strabo), pottery and coins, McCredie argues the camps, both on hills with nearby beaches, were built by Ptolemy’s forces around 265BC.

Dekeleia and Ancient Aphidna

A prominent hill, now covered in pines, which once hosted a Spartan military camp. Today part of the scenic Tatoi royal estate, Dekeleia is remarkable for being one of the few forts that can be connected with a known historical event: its Spartan takeover and fortification in 413BC at the suggestion of Alcibiades. The walls were once about 2m thick with a total length of about 800m.

Earlier surveys showed that Kotroni hill was occupied repeatedly from the Middle Bronze Age through Byzantine times. McCredie suggests that the Aphidna citadel with its rough fieldstone masonry was never one of Attica’s premier garrison-fortresses, like the ashlar-built installations at Rhamnous, Phyle and elsewhere.

Phyle

Located northwest of Phili village, ancient Phyle is one of the most impressive ancient fortresses in Attica. Perched on a crag at an elevation of 680m, the massive, early 4th century BC walls are preserved to a height of more than 4m and feature one circular and two rectangular bastions.

Upon their return to Phyle, however, the Spartans were ambushed in an early-morning attack on their camp. Thrasybulus’ army had swelled from 70 to 700 during their brief absence and this inspired force inflicted 120 Spartan losses; the Athenians lost three soldiers. The momentum gained from the victory at Phyle carried Thrasybulus and his rapidly expanding army to another victory a few days later at Piraeus, where their defeat of the Spartans and killing of Critias, leader of the oligarchs, soon led to The Thirty’s flight to Eleusis and the restoration of democracy in Athens.

Hymettus fort, a trace of enemies past

In 1805, while climbing Mt Hymettus, Irish painter and traveller Edward Dodwell stumbled across the low remains of an ancient, walled military camp, which he mistakenly supposed was the site of a town.

With a commanding position overlooking Athens, and plentiful water at nearby Kesariani, this little-known fort on Hymettus was, according to specialist James McCredie, “a good temporary camp for a force attacking the city”.

Author: John Leonard | Source: Athens News [December 25, 2011]