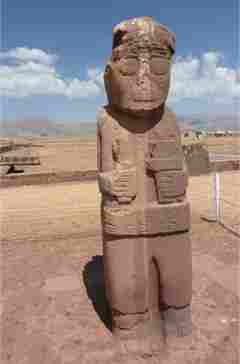

On the vast, dry Bolivian plains near the shore of Lake Titicaca stand the remains of a great civilization. The glaring sun beats down on red stone walls and statues that have withstood more than 1,000 years.

This is the City of Tiwanaku, center of a civilization that reached its height between 600 and 1000 A.D., well before the Inca and Spanish conquests of the area.

This is the City of Tiwanaku, center of a civilization that reached its height between 600 and 1000 A.D., well before the Inca and Spanish conquests of the area.

What remains of Tiwanaku are ruins of the ceremonial center of one of the greatest civilizations in the Americas at its time. At its most powerful, Tiwanaku’s influence stretched over parts of modern day Bolivia, Chile and Peru.

The city’s center, full of beautifully carved stone doorways and figures, was surrounded by a community of 15,000 to 20,000 indigenous artisans and farmers whose adobe homes stretched over the flat land.

The city’s center, full of beautifully carved stone doorways and figures, was surrounded by a community of 15,000 to 20,000 indigenous artisans and farmers whose adobe homes stretched over the flat land.

When Inca forces moved down into Bolivia from their strongholds in Peru in the 1400s, they found Tiwanaku deserted.

For the Inca, the Spanish, and the many researchers who have studied the ruins in recent decades, Tiwanaku is a point of fascination. The skill and creativity its makers displayed speak of a complex civilization that melted away.

For the Inca, the Spanish, and the many researchers who have studied the ruins in recent decades, Tiwanaku is a point of fascination. The skill and creativity its makers displayed speak of a complex civilization that melted away.

“Tiwanaku has a very strong attraction,” said Bolivian archaeologist Jedu Sagarnaga. “There was a Spaniard who said ‘Nobody passes here without feeling the attraction of the ruins.’ They are like a magnet.”

Bolivia’s 1952 social revolution led to Tiwanaku’s rebirth as an important symbol of indigenous culture and tradition. The revolution won new rights for Bolivia’s indigenous, like the right to vote, go to school and own land. Nicole Couture is an anthropologist and professor at McGill University who has studied Tiwanaku for 20 years.

Bolivia’s 1952 social revolution led to Tiwanaku’s rebirth as an important symbol of indigenous culture and tradition. The revolution won new rights for Bolivia’s indigenous, like the right to vote, go to school and own land. Nicole Couture is an anthropologist and professor at McGill University who has studied Tiwanaku for 20 years.

“It was a time of fundamental transformation when the Bolivian nation finally included its indigenous population, and that is reflected in a new attention being paid to Tiwanaku,” Couture said. “Tiwanaku becomes a symbol of the new and inclusive national identity – that includes the indigenous past.”

Archaeologists are divided on who created Tiwanaku, and why they ultimately abandoned the extraordinary city. Some academics believe the same Aymara people who today populate Bolivia’s plains built Tiwanaku, while others think its creators have long since dispersed and left the area.

Archaeologists are divided on who created Tiwanaku, and why they ultimately abandoned the extraordinary city. Some academics believe the same Aymara people who today populate Bolivia’s plains built Tiwanaku, while others think its creators have long since dispersed and left the area.

Drought may have devastated crops and starved the city, and strife between groups in the area could have pulled the society apart and ended it. There are even people who believe Tiwanaku was built by aliens, or that it is the result of a collision with the moon.

But Tiwanaku was a very human city where religion, politics and celebrating combined on a grand scale, said Alexei Vranich, archaeologist at the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Tiwanaku must have been an impressive place of ritual political importance, with a lot of beer and a lot of food.”

But Tiwanaku was a very human city where religion, politics and celebrating combined on a grand scale, said Alexei Vranich, archaeologist at the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Tiwanaku must have been an impressive place of ritual political importance, with a lot of beer and a lot of food.”

That Tiwanaku produced a lot of food is one thing many archaeologists do agree on. Bolivia’s altiplano is a place of extremes. The sun burns unopposed by thin, high-altitude air during the day, and nights can be freezing cold. According to research by anthropologist Alan Kolata of the University of Chicago, the people of Tiwanaku built raised fields where they grew quinoa, wheat and other crops. These methods were so successful that agricultural surpluses contributed to the society’s power.

Today, the site draws thousands of visitors each year, and continues to gain force as an emblem of indigenous, particularly Aymara, identity. Bolivia’s Aymara Indian President Evo Morales was sworn into his second term as president at Tiwanaku.

Today, the site draws thousands of visitors each year, and continues to gain force as an emblem of indigenous, particularly Aymara, identity. Bolivia’s Aymara Indian President Evo Morales was sworn into his second term as president at Tiwanaku.

The site also sees a huge celebration at the winter solstice, when Bolivians and tourists celebrate all night and watch the sun rise over the ruins. Nelli Mayta, an Aymara Indian from La Paz, is amazed at how the celebration has grown over the years, and how many foreigners now attend it.

But all is not bliss in Tiwanaku. Conflicts between local and regional government over money mean the site’s two museums are in disrepair. There are also disagreements on how to care for the ruins. Many archaeologists agree that the site needs major investment and professional engineering and restoration.

But all is not bliss in Tiwanaku. Conflicts between local and regional government over money mean the site’s two museums are in disrepair. There are also disagreements on how to care for the ruins. Many archaeologists agree that the site needs major investment and professional engineering and restoration.

On the edges of Tiwanaku’s tourist areas stone doorways are propped up with branches, and blocks of stone have been dragged and arranged haphazardly. Restorations-in-progress leave large trenches near what was once a ceremonial pyramid. While Tiwanaku’s symbolic power is definite, the future of the ruins seems uncertain.

Author: Sara Shahriari | Source: Indian Country Today [December 29, 2010]