The exhibit will surprise viewers who think of the Horn of Africa as a mostly Islamic area. In fact, Christianity reached Ethiopia in the fourth century of the Common Era, and about 65 percent of the country's people practice an orthodox form of the faith.

An authority on archeaology in Greece, Nicgorski has yet to visit Ethiopia. She was drawn to the topic by McKenzie, who wanted to display the Ethiopian collection of the Rev. Thomas Yurchak.

Nicgorski and McKenzie visited Yurchak at St. Jude Catholic Church in Eugene to view his Ethiopian icons. "It was like Christmas," she said. "He has a wonderful collection."

icons, crosses and at the Hallie Ford Museum

[Credit: FRANK MILLER|Special to the Statesman Journal]

The simplest icons in the show are carved wood, small enough to hold in one's hand. The right-hand panel of a typical one shows a suffering Jesus on the cross, with his mother and the apostle John grieving alongside. Stars fall from the sky as squiggly lines. On the facing panel, Jesus carries a triumphant banner to indicate that he has risen. Angels float on clouds while the evildoers — shown in profile, Ethiopian code for villains — are padlocked into hell.

Variations on this icon add more doors, becoming as elaborate as the two-tiered tower decorated with 24 scenes at the show's entrance. The figures of three old men — the Father, Son and Holy Spirit — occupy the top niche in this piece, presiding over the Gospel history below.

Viewers who find the Print Study Gallery — after a detour through the Mark and Janeth Sponenburgh Gallery — will be rewarded by the sight of some saints and practices unknown in Western tradition. For instance, there's a small icon for Gäbrä Mänfäs Qeddus, one of the most revered Ethiopian saints. He is supposed to have lived for 562 years without eating or drinking, a feat suggested by his body-length beard.

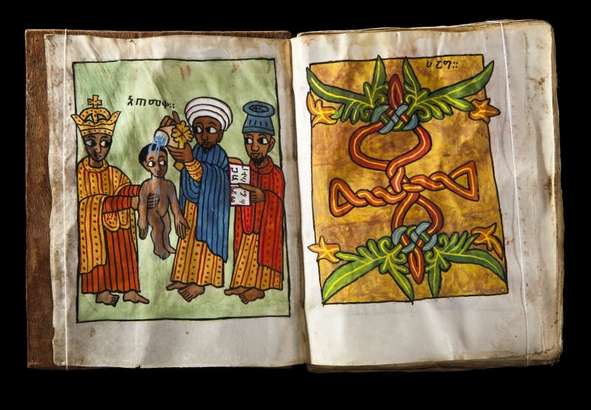

Lovely illuminated manuscripts suggest Western works from the Middle Ages — but these small prayer books are by contemporary scribes who keep the old traditions alive.

Nicgorski hopes that many people will visit the show, even if they're new to the Hallie Ford museum. "This is a unique opportunity to see art from Africa and particularly from Ethiopia," she said. "The history of Christianity in Ethiopia is pretty remote from the Pacific Northwest. This is an opportunity to learn about an ancient Christian tradition."

The exhibition "Glory of Kings: Ethiopian Christian Art From Oregon Collections" is hosted by the Study Gallery and Print Study Gallery of Willamette University's Hallie Ford Museum of Art, 700 State St. through June 12.

Author: Barbara Curtin | Source: Statesman Journal [April 25, 2011]