Ice Age paintings and carvings in Europe are revered as sublime achievements of early humans, yet the prehistoric rock art in the American West is far less known. At Legend Rock in central Wyoming, 10,000 years of profound beliefs are inscribed on red sandstone cliffs.

As the Pleistocene period ended approximately 12,000 years ago with the passing of the last Ice Age, people were spreading from Asia to North America and south into what is now the U.S. Archaeologists have found evidence that the early immigrants took advantage of the moderating climate to cross the high passes of the Tetons and Absaroka mountains to settle among their foothills and what are now the broad, arid plains encircled by these peaks on the west and north and by the Bighorn and Owl Creek ranges to the east and south. Near the center of this basin stretching across more than 60 miles stands Legend Rock.

As the Pleistocene period ended approximately 12,000 years ago with the passing of the last Ice Age, people were spreading from Asia to North America and south into what is now the U.S. Archaeologists have found evidence that the early immigrants took advantage of the moderating climate to cross the high passes of the Tetons and Absaroka mountains to settle among their foothills and what are now the broad, arid plains encircled by these peaks on the west and north and by the Bighorn and Owl Creek ranges to the east and south. Near the center of this basin stretching across more than 60 miles stands Legend Rock.

Rising 200 feet above the Cottonwood creek that runs near its base, Legend Rock is a cliff face over 800 yards long. It is carved with nearly 300 images scattered along its length. They are petroglyphs that archaeologists now believe range in date from about 11,000 years ago to perhaps the mid-19th century. The oldest documented images at the site are carvings of an antelope, a human figure and a life-size adult hand. The antelope and full figure are primarily rendered as outlines chipped, stroke by stroke, into the rock with a harder stone. The picture of a human hand with fingers splayed was more laboriously rendered by pecking away the entire rock surface within the boundaries of the fingers and palm. It looks as if a clay-covered hand has just been pressed to the rock.

Rising 200 feet above the Cottonwood creek that runs near its base, Legend Rock is a cliff face over 800 yards long. It is carved with nearly 300 images scattered along its length. They are petroglyphs that archaeologists now believe range in date from about 11,000 years ago to perhaps the mid-19th century. The oldest documented images at the site are carvings of an antelope, a human figure and a life-size adult hand. The antelope and full figure are primarily rendered as outlines chipped, stroke by stroke, into the rock with a harder stone. The picture of a human hand with fingers splayed was more laboriously rendered by pecking away the entire rock surface within the boundaries of the fingers and palm. It looks as if a clay-covered hand has just been pressed to the rock.

These carved images nearly blend into the deep reddish purple of the stone's surface because both stone and engraving have accumulated layers of minerals over the millennia. This patina enables scientists to estimate the date of the carvings. In the case of the handprint, 10,700 years ago, with an error range of plus or minus 1,400 years. Adjacent engravings are dated to about 6,800 years ago. While all of these are relatively small images and show only essential shapes of their subjects, many others at Legend Rock are far larger and more richly detailed.

These carved images nearly blend into the deep reddish purple of the stone's surface because both stone and engraving have accumulated layers of minerals over the millennia. This patina enables scientists to estimate the date of the carvings. In the case of the handprint, 10,700 years ago, with an error range of plus or minus 1,400 years. Adjacent engravings are dated to about 6,800 years ago. While all of these are relatively small images and show only essential shapes of their subjects, many others at Legend Rock are far larger and more richly detailed.

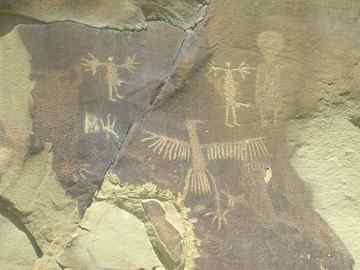

These monumental figures, standing almost five feet tall, are the dominant images of the cliff walls. Unlike the earliest carvings, they are not naturalistic, but depict fantastic, anthropomorphic personages. Generally dated to approximately 2,000 years ago, they both evince the importance of this site over many millennia and offer clues to its meanings for the early inhabitants who were devoted to it.

These monumental figures, standing almost five feet tall, are the dominant images of the cliff walls. Unlike the earliest carvings, they are not naturalistic, but depict fantastic, anthropomorphic personages. Generally dated to approximately 2,000 years ago, they both evince the importance of this site over many millennia and offer clues to its meanings for the early inhabitants who were devoted to it.

Until recently, archaeologists believed that the Shoshone people, many of whom now live on the Wind River Reservation near Legend Rock, had entered the area only a few hundred years before Europeans arrived. (The Shoshone are probably best known through Sacagawea, the woman who aided Lewis and Clark during their 1803-06 expedition to the Pacific.) New research into language groups and excavations has provided convincing evidence that the Shoshone arrived thousands of years earlier and that they or their predecessors may well have made the carvings on Legend Rock. If so, the Shoshone may offer the greatest insight into the images. To them, Legend Rock is a sacred place, where individuals communed with spirit worlds.

Until recently, archaeologists believed that the Shoshone people, many of whom now live on the Wind River Reservation near Legend Rock, had entered the area only a few hundred years before Europeans arrived. (The Shoshone are probably best known through Sacagawea, the woman who aided Lewis and Clark during their 1803-06 expedition to the Pacific.) New research into language groups and excavations has provided convincing evidence that the Shoshone arrived thousands of years earlier and that they or their predecessors may well have made the carvings on Legend Rock. If so, the Shoshone may offer the greatest insight into the images. To them, Legend Rock is a sacred place, where individuals communed with spirit worlds.

To invoke human and animal spirits and receive their powers, a person might spend days in an arduous ritual at the base of one of the figures inscribed on Legend Rock. Traditionally, the Shoshone believe the images were not made by humans but by the spirits they not only represent but embody. In this context, the chipped forms offer vital portals to other realities.

To invoke human and animal spirits and receive their powers, a person might spend days in an arduous ritual at the base of one of the figures inscribed on Legend Rock. Traditionally, the Shoshone believe the images were not made by humans but by the spirits they not only represent but embody. In this context, the chipped forms offer vital portals to other realities.

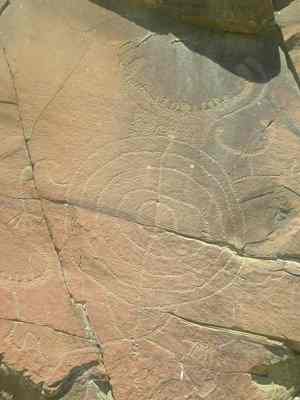

Although the figures cannot be identified with confidence, they do suggest both ideas of passage and tangible connections between the imaginations that conceived these designs and the hard rock of the fractured ledges. One carved figure includes a feature common at the site, a head topped by a "U" shape, possibly the horns of a spirit combining man and beast. In this case, the body is also composed of curves. A series of concentric circles is bisected vertically by an incised line and horizontally by a crack in the rock face. Further integrating figure and rock, arms and legs extend until they inflect and metamorphose as they cross other fractures in the stone—as if the figure had crossed an imaginative as well as a physical divide. These crisply incised lines describe forms every bit as distinct and revelatory as the graphic inventions European artists, such as Joan Miró, derived from prehistoric art. Yet here there is no doubt these otherworldly images are deeply rooted in the reality of Legend Rock.

Although the figures cannot be identified with confidence, they do suggest both ideas of passage and tangible connections between the imaginations that conceived these designs and the hard rock of the fractured ledges. One carved figure includes a feature common at the site, a head topped by a "U" shape, possibly the horns of a spirit combining man and beast. In this case, the body is also composed of curves. A series of concentric circles is bisected vertically by an incised line and horizontally by a crack in the rock face. Further integrating figure and rock, arms and legs extend until they inflect and metamorphose as they cross other fractures in the stone—as if the figure had crossed an imaginative as well as a physical divide. These crisply incised lines describe forms every bit as distinct and revelatory as the graphic inventions European artists, such as Joan Miró, derived from prehistoric art. Yet here there is no doubt these otherworldly images are deeply rooted in the reality of Legend Rock.

A National Historic Site since 1973, Legend Rock is only beginning to be deciphered by archaeologists and scientists working with the peoples who have long revered it. Together with many other rock-art locations across the western U.S., it demonstrates that America, too, has a rich and ancient cultural history. Moreover, Legend Rock is linked by technique and imagery to sites around the world—Twyfelfontein in Namibia, Ningxia in China, and Alta in Norway, to name a few—all made by burgeoning human populations after the glaciers receded and the modern world began to take shape.

A National Historic Site since 1973, Legend Rock is only beginning to be deciphered by archaeologists and scientists working with the peoples who have long revered it. Together with many other rock-art locations across the western U.S., it demonstrates that America, too, has a rich and ancient cultural history. Moreover, Legend Rock is linked by technique and imagery to sites around the world—Twyfelfontein in Namibia, Ningxia in China, and Alta in Norway, to name a few—all made by burgeoning human populations after the glaciers receded and the modern world began to take shape.

Author: Michael FitzGerald | Source: Wall Street Journal [September 19, 2010]