In France at the end of the 19th century, archaeologists and the general public discovered – amid a flurry of images, designs, gold and colours – the civilisations that have occupied Greece over millennia. Both archaeological science and modern art were profoundly affected.

This journey back in time presents some striking personalities, geologists, archaeologists and enlightened amateurs who explored the Greek soil using methods and ideas that recall the various luminaries of Jules Verne, ever confident in progress and the progress of science.

After the pioneers who travelled across the Cyclades and paved the way for the discovery of the first remains on the island of Santorini, two men stand out for being both exceptionally gifted and imaginative, talented scientists and great visionaries: Heinrich Schliemann and Arthur Evans. They wrote a different history of Greece that long pre-dated the classical period on the basis of their excavations in Troy (Asia Minor), Mycenae (Greece) and Knossos (Crete).

These fabulous discoveries were spread throughout France by the academic world. Salomon Reinach, then director of the Musée des Antiquités Nationales, and his friend Edmond Pottier, curator at the Musée du Louvre, did their best to introduce the visiting public to original objects and reproductions that were characteristic of the art of these «Aegean» civilisations.

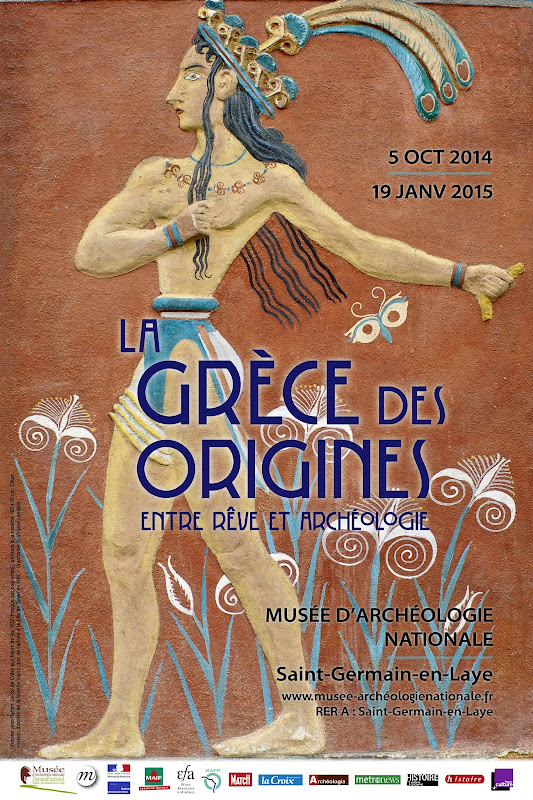

The visitors of the exhibition are even able to discover, for example, the most beautiful objects from the Greek museums thanks to spectacular reproductions by Emile Gilliéron, presented exceptionally at Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

But Schliemann and Evans were modern men and broadcast their discoveries using every possible medium: books, newspaper articles, photographs and drawings. This is how Mycenae and Knossos became the new fashionable travel destinations where artists like Léon Bakst went to draw inspiration from a new, vibrant and colourful art. Theatre or opera scenery, costumes, dresses and scarves celebrated by Marcel Proust will tell visitors about the «Cretomania» that swept through Paris.

Archaeologists now have a different view of these civilisations, which were discovered more than a century ago: their methods have changed, as have their questions, and it is important to know that archaeology is also built on hypotheses – or even illusions – that sometimes need to be deconstructed.

Yet it is essential that we continue to imagine the past of the peoples of the Aegean Sea. Artistic creations, whether by fashion designers like Karl Lagerfeld or by filmmakers or comic strip artists, are still imbued with octopuses and rose patterns, goddesses with serpents, red columns and golden masks.

Source: Musée des Antiquités Nationales [December 13, 2014]