Imagine, for one moment, that first shock of recognition when the creatures of the cave wall at Chauvet in the Gorges de L'Ardeche were exposed to artificial illumination and human consciousness for the first time in thousands of years.

The date is December 18, 1994. Here is Jean-Marie Chauvet, the archaeologist who discovered the caves, recalling the impact of those long-forgotten dream images: "Time was abolished, as if the tens of thousands of years that separated us from the producers of these paintings no longer existed.

The date is December 18, 1994. Here is Jean-Marie Chauvet, the archaeologist who discovered the caves, recalling the impact of those long-forgotten dream images: "Time was abolished, as if the tens of thousands of years that separated us from the producers of these paintings no longer existed.

Deeply impressed, we were weighed down by the feeling that we were not alone; the artists' souls and spirits surrounded us. We thought we could feel their presence; we were disturbing them."

Until recently, radiocarbon dates suggested that Chauvet contained the oldest Paleolithic cave art yet discovered - dating back an astonishing 35,000 years. Many books have been published hailing Chauvet as "the birthplace of art".

In a soon-to-be published paper, however, a French radiocarbon specialist argues that charcoal originally used for radiocarbon dating was contaminated by material from much earlier cave-bear bones.

His research indicates a date in line with much other Paleolithic art in Europe , with most of the images dating from between 20,000 and 15,000BCE. Not that it takes anything away from Chauvet's breathtaking galleries. The sheer time depth embedded in its pigment remains a dizzying concept - a passage of lifetimes that sears the mind almost as sharply as the images themselves.

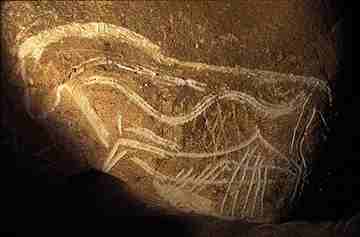

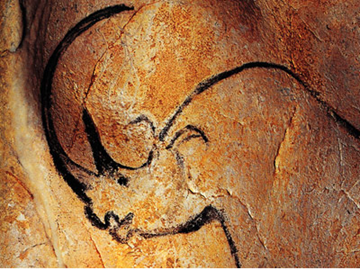

At Chauvet, veiled for much of the year in pitch darkness, images common to all European cave art - mammoths, reindeer, horses, cattle, as well as hand prints and hand silhouettes - float among rarer cave beasts: bears, lions, hyenas, an owl - its head turned 180 degrees.

At Chauvet, veiled for much of the year in pitch darkness, images common to all European cave art - mammoths, reindeer, horses, cattle, as well as hand prints and hand silhouettes - float among rarer cave beasts: bears, lions, hyenas, an owl - its head turned 180 degrees.

Elsewhere, there is a bear's skull on a stone "altar", and in the deepest part of the cave, in the so-called "Sorcerer's chamber", a half-man, half-bison figure leaps out of the rock, paired with an older depiction of a woman, the lower half of her body strongly accentuated.

We can never know what power these figures exerted on their makers; our closest resource is, perhaps, the power they retain over us. As the sculptor John Robinson found on the first of several descents into Chauvet as a representative of the Bradshaw Foundation, these prehistoric markings remain extraordinarily fresh.

"I took out my binoculars and studied the Sorcerer," he wrote in his account of his first trip in 1999. "The lens intensified the light and made the figure leap into life. I was in the presence of a deity living on Earth. He radiated a ferocious pagan power."

Though most archaeologists balk at describing the cave art in such terms, the ideas of David Lewis-Williams come close to embracing them. Lewis-Williams is an expert on San Bushman culture and the professor emeritus of cognitive archaeology in Johannesburg , and argues that the art has its source in human neurology and shamanism.

Though most archaeologists balk at describing the cave art in such terms, the ideas of David Lewis-Williams come close to embracing them. Lewis-Williams is an expert on San Bushman culture and the professor emeritus of cognitive archaeology in Johannesburg , and argues that the art has its source in human neurology and shamanism.

"Archaeologists talk about the evolution of intelligence," he says, "but the evolution of consciousness is even more important." And the recognition and making of two-dimensional images, he suggests, reflects that evolution.

He recalls a recent visit to the cave at Mas d'Azil in the Pyrenees: "squeezing and crawling through, and as you lie in the tunnel, right above you there are the engravings. What were these people up to?" he asks.

"Why did they feel they had to crawl all these distances to make their images? I think the only answer is that they did it because that's where the images were. They were looking for them. They thought these images were deep underground."

Central to Lewis-Williams's thesis is the role of altered neurological states in the making and meaning of Paleolithic art. At Chauvet, as in many other locations, the bestiary is accompanied by many abstract lines and scorings - spots, lines, zigzags, grids, circles - the kind of visual interference Lewis-Williams associates with accounts of trance and altered states.

Central to Lewis-Williams's thesis is the role of altered neurological states in the making and meaning of Paleolithic art. At Chauvet, as in many other locations, the bestiary is accompanied by many abstract lines and scorings - spots, lines, zigzags, grids, circles - the kind of visual interference Lewis-Williams associates with accounts of trance and altered states.

These, in turn, gave way to images of animals - largely the same repertoire for many millennia - that were long held in the mind before they appeared, seemingly fully formed, on the cave wall.

"You have people penetrating underground, going into the very entrails of the underworld, making pictures coming out of cracks, suggesting that the rock face is permeable." That rock face, he argues, acted as a membrane to a supernatural world that was held in the mind of shamanic figures.

They are compelling ideas, supported chiefly by Jean Clottes, the director of research at the cave since its discovery until 2004.

Other specialists are sceptical: "It does happen in some ethnographic contexts," says Professor Colin Renfrew, widely regarded as one of the world's leading prehistorians, "but there really is no evidence for it in the Upper Paleolithic. He's built up a big theory from one personal approach. I am one of those who is sceptical of that approach. I don't think it helps."

While theories about its art and antiquity abound, visitors to Chauvet are rare. Other caves such as Pech Merle, discovered by two teenage boys in 1922, remain open to the public, but few will ever know the experience of descending the 30-foot drop to Chauvet's first chamber.

While theories about its art and antiquity abound, visitors to Chauvet are rare. Other caves such as Pech Merle, discovered by two teenage boys in 1922, remain open to the public, but few will ever know the experience of descending the 30-foot drop to Chauvet's first chamber.

For those of us stranded above ground, the film director and veteran of extreme environments, Werner Herzog, has been there for us with a 3D camera crew to evoke Chauvet's Paleolithic underworld of mystery and imagination.

His forthcoming film Cave of Forgotten Dreams promises a compelling 3D journey into the cave complex and an image tradition that, with minor modulations, would continue unchanged for many thousands of years, their potency for the makers evidently undimmed, their kinetic impact disarmingly fresh.

"It is remarkable that there are centuries, indeed millennia, of use of the caves, and there's certainly a continuous knowledge of them," says Renfrew. "Ten thousand years may separate what may be almost the same image. And that is an extraordinary thing. If you look 10,000 years back from our present time, things are rather different."

What were those meanings that persisted for so long? What was their purpose? Why were people compelled to journey up to a kilometre underground to make and to see? It is one of archaeology's great mysteries. It was once thought to be an example of sympathetic magic - rendering your hunting goal then going to get it. But as Renfrew points out, many of the animals are not those they actually hunted.

What were those meanings that persisted for so long? What was their purpose? Why were people compelled to journey up to a kilometre underground to make and to see? It is one of archaeology's great mysteries. It was once thought to be an example of sympathetic magic - rendering your hunting goal then going to get it. But as Renfrew points out, many of the animals are not those they actually hunted.

And if they were the totems of a unifying religion, why is the art in such inaccessible places? "If it wasn't religion that drove them underground, what could it have been?" asks Lewis-Williams. "I can't think of any secular reason why people would travel over a kilometre underground to make these pictures.

Renfrew, however, points to a lack of evidence for distinct ritual or religious use and suggests a more practical, if not wholly secular purpose. "They're not places of assembly in the way that most religious meeting places are," he argues. "You don't have much evidence in any of the caves of rituals, or rituals of burial."

Instead, he cites John Pfeiffer's 1982 study, The Creative Explosion. "I think one of the best suggestions or explanations was that they were used in educating the young, maybe in initiation ceremonies, where one or two people would go at a time. Initiation," he continues, "is probably a better way of thinking rather than of profound religious ceremonies."

Instead, he cites John Pfeiffer's 1982 study, The Creative Explosion. "I think one of the best suggestions or explanations was that they were used in educating the young, maybe in initiation ceremonies, where one or two people would go at a time. Initiation," he continues, "is probably a better way of thinking rather than of profound religious ceremonies."

An initiation ceremony, of course, can be a terrifying, overwhelming experience, a challenge to self and senses, fulfilling both utilitarian and ritual purposes. Did Chauvet's Paleolithic visitors, at some point on their journey, extinguish their charcoal torches to experience the underworld beyond the senses?

Did Herzog cut the lights, during filming, even if just for a few moments? 'The darkness there is absolutely total,' says Lewis-Williams of the unilluminated cave experience. "A couple of times I've sat in the dark, and after a few minutes, utter silence and utter, utter darkness. You get the disembodied feeling that you're almost floating in nothingness."

But to the darkness they brought light, colour, line and art. And though no musical instruments have been found at Chauvet, we do know that music was made in caves. There is evidence of stalactites being struck to make resonant gong-like sounds, and flutes hollowed from birds' wings, bone and ivory have been found embedded in cave floors.

But to the darkness they brought light, colour, line and art. And though no musical instruments have been found at Chauvet, we do know that music was made in caves. There is evidence of stalactites being struck to make resonant gong-like sounds, and flutes hollowed from birds' wings, bone and ivory have been found embedded in cave floors.

When one of them was reconstructed, it played the diatonic scale of Do Re Mi - the familiar sound of an old tune heard long ago.

And so our vast timescale evaporates in the sound of music, and the pigments of the Palaeolithic image maker. See their work, and you feel their presence, as if they were standing right next to us, the way Jean-Marie Chauvet felt on first encountering the images on the cave wall when he thought he could feel their presence, and that he had disturbed them.

Author: Tim Cumming | Source: The National [December 27, 2010]